Subscribers make this coverage and analysis possible.

Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale is often understood to closely share in the dystopian futurism of George Orwell’s 1984. Both books examine the way totalitarian governments use repressive cultural hegemony, disinformation, and state violence to control populations in the name of dubious utopian ideologies.

They also share the distinction of being frequently banned and challenged in the school setting. The Handmaid’s Tale has been subject to at least 60 recent bans across the country in recent years, significantly more often than the also-frequently-banned 1984.

Orwell’s novel— loosely based on the similarly-plotted WE, by Yevgeny Zamyatin (which was, not incidentally, immediately banned in post-revolutionary Russia)— can be most obviously read as a projection of the specific policies of 1940’s-era European fascists onto an indeterminate, distant future Britan. On the other hand, Atwood’s novel is a detailed meditation on what a fascist, specifically white Christian nationalist regime could look like in the very near, specifically American future (relative to the book’s 1985 publication) likely taking place in the early 1990s.

In this way, it is probably more comparable to Octavia Butler’s 1993 novel Parable of the Sower, a book that projects economic and environmental collapse in near-future America.

A novel about history and contemporary society

Atwood derived the details in her novel from both historical and contemporary totalitarian, theocratic, and/ or fascist regimes. She has explicitly given examples from the Romanian government of Nicolae Ceaușescu, which (in a preview of current Hungarian policies under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán) used state pressure to coerce women into becoming pregnant.

Another inspiration was the 1979 Iranian revolution, which led to the creation of a new theocratic regime (if more democratic than the novel’s Gilead), seems like a clear antecedent, with its focus on rolling back women’s rights in the name of state-mandated religious purity.

But, crucially, Atwood was not simply wondering what would happen if foreign totalitarianism came to America. America, after all, has at times been the inspiration for fascists worldwide. (The Nazis’ framing of eugenics, forced sterilization, prohibitions against “race-mixing”, and their plans for violently segregating targeted communities, were explicitly modeled on US policies, and on the Jim Crow- era American South.) Atwood also mentions an article about the Ku Klux Klan as part of the gestational material of the book, and as she noted herself, “In 1985 racists in the US were preaching revolution: ‘US conservatives push new order – the push to the right.’”

The book is also explicitly ground in the near future because unlike 1984’s Winston Smith, who can just barely remember a childhood that was somewhat different, Atwood’s unnamed protagonist (called “Offred,” as in of Fred, because handmaids are forced to take on diminutives of their captors’ names) clearly remembers a life when egalitarian and feminist reforms were a part of society. (In this way, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis depicts a revolutionary period in early-1980’s Iran that is very similar to the one “Offred” has recently experienced as The Handmaid’s Tale begins. It is probably no coincidence that both books are among the most frequently-banned in the US.)

A warning about fascism

The Handmaid’s Tale is often understood to be a book about reproductive rights. The book certainly foregrounds the way women in Gilead have been reduced in status to either mothers or delivery systems for babies. A fertility crisis threatens the perceived value of the women of the ruling regime— in other words, their value as wives and mothers— and provides the regime its rationale for the systemic sexual assault of “handmaids”.

That said, this choice to foreground the specific oppression of women reflects broader themes in the way real-life fascist regimes operate.

In How Facism Works, philosopher Jason Stanley writes about how fascist governments rely on patriarchal “traditional” family roles to bolster a view of a country run by a “father” figure. For example, he quotes original Nazi propaganda chief Gregor Strasser as saying, “for a man, military service is the most profound and valuable form of participation— for the woman it is motherhood!”

Or, as “Offred” explains, “There is no such thing as a sterile man anymore, not officially. There are only women who are fruitful and women who are barren, that’s the law.”

Later, Stanley writes, “Fascist propaganda promotes fear of interbreeding and race mixing, of corrupting the pure nation with, in the words of Charles Lindbergh [ca. 1939], speaking for the America First movement, ‘inferior blood’.” (Stanley quotes an especially horrifying instance of this fear in action: “The South Carolina senator Benjamin Tillman said on the floor of the Senate that ‘the poor African has become a fiend, a wild beast seeking whom he may devour, filling our penitentiaries and our jails, lurking around to see if some helpless white woman can be murdered or brutalized’”.

White supremacists throughout American history have used this depiction of the supposed sexual savagery of Black Americans to justify their persecution, arrest, and murder. Tilman, famously, bragged about murdering Back South Carolinians as part of a white supremacist militia.

So the problem with Gilead is not just that it oppresses (specifically white) women— which it does, brutally— or that it oppresses racial minorities— who are, in the novel, essentially absent from society1— or that it rejects LGBTQ+ people as “gender traitors” (like “Offred’s” friend Moira, an out lesbian before the rise of Gilead)— but that it does all of this in order to exercise total control over everyone in society. Everyone is either a prisoner of strict gender roles (as well as implicit class distinctions) or the beneficiary (and, perhaps, simultaneous victim, with the character of Nick, a “Guardian” of the regime who becomes Offred’s lover, being one clear example) of the system that maintains those roles.

The historical context of The Handmaid’s Tale— where a theocratic, fascist regime gains power through a performative backlash against social progress (in this case, the third wave feminism and gay rights movements)— has gained renewed resonance in recent decades, which have seen a politics driven by an explicit backlash against feminist, anti-racist, and LGBTQ+ rights movements. (The ruling class of Gilead would have looked on Project 2025’s Mandate for Leadership— with its plans to outlaw “pornography,” deny “gender ideology,” and restrict reproductive health far beyond simply outlawing abortion— approvingly, as a first step towards utopia.)

In South Carolina, which has currently banned more books from schools than any other state in the country, The Handmaid’s Tale is likely next.

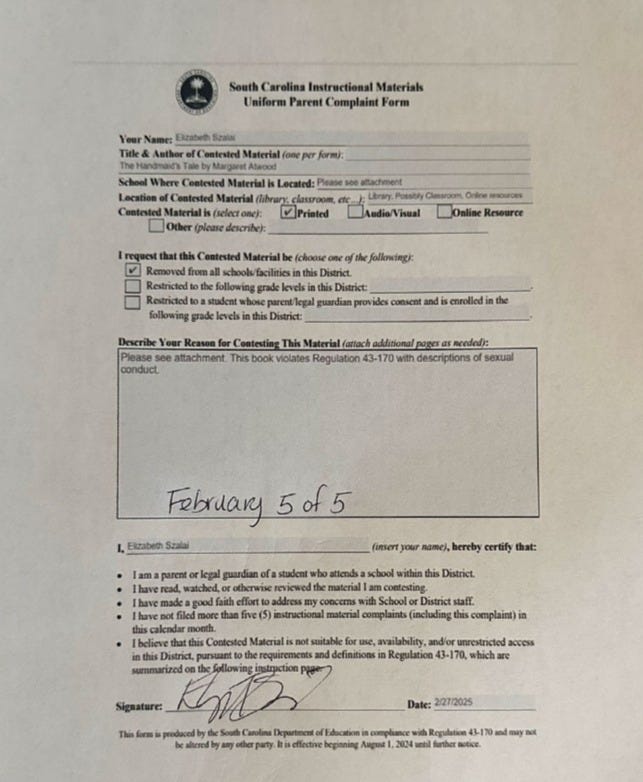

The majority of the books which have been banned at the state level in South Carolina have resulted from challenges by one individual, Elizabeth “Ivey” Szalai of Beaufort County, who challenged 97 books in that district. The school district in Beaufort underwent a lengthy committee process to consider every one of those challenges, ultimately removing five books and retaining 92.

I previously filed a FOIA request to obtain the committee analysis and vote on The Handmaid’s Tale, which the district ultimately retained for use by high school students. One of the reviewers in Beaufort called the novel “A fictional account of how a society can be overtaken, and change from a democracy to a dictatorship very suddenly”.

Several committee members voted to return the book only to high school students; none of the members voted to uphold the removal of the book from all district schools.

Yet, as multiple members of the State Board of Education complained at their April meeting, “someone from Beaufort”— Szalai— was functionally directing the entire state’s policy on book bans.

The district’s response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request from Families Against Book Bans (FABB) suggests that Szalai has been making her way through the 92 books the district chose to leave on the shelves and asking the district to re-litigate each one.

For each book the district chooses not to reconsider, the complainant can take her case to the State Board, which then has the option to retain the book for all students, remove it for all students, or restrict it with parental approval. (Thanks to a last-minute amendment to Regulation 43-170, the Board’s book ban regulation, individuals are limited to five book challenges per month.) The Board has only moved to restrict one book to date, Ellen Hopkins’ CRANK. Every other book has either been retained or removed completely from all state schools.

In January 2025, Szalai contacted the district to challenge, for the second time, five of the last ten books considered by the Board, according to the FOIA response. When the district declined to undergo the process again, the challenges were taken up by the State Board. All ten were ultimately removed from every school in the state.

In February, Szalai filed to re-litigate five more: Milk and Honey, by Rupi Kauer; November 9, by Colleen Hoover; Oryx and Crake, also Atwood; Perfect, by Ellen Hopkins (the state’s most-banned author, with five books already banned and one restricted), and The Handmaid’s Tale.

Assuming the complainant and the Board continue the current pattern, these would likely be the next five books the Board considers.

But whether it bans the Handmaid’s Tale is somewhat up in the air.

Prior to the passage of the state regulation, the book had already been removed by Anderson School District One and Spartanburg District One, and challenged by residents in at least two other South Carolina school districts.

In response to moves to ban The Handmaid’s Tale from Anderson schools in 2023, Sandy Senn, who was then a Republican state senator (and one of the “sister senators” who opposed the state’s near-total abortion ban), said, on the SC Senate floor, “We have extremists who are trying to take away a book. I read it for the first time right after law school. It’s been around forever.”

The Instructional Materials Review Committee is currently several days behind schedule on posting an agenda for the coming month— it did not meet last month— and has not posted any information about future instructional materials considerations.

Off the record, some Board members have reportedly indicated that they are encouraging Beaufort Schools to review the remaining books challenged by Szalai, perhaps to give themselves a reprieve from negative attention and publicity.

As the FOIA responses from Beaufort show, the Beaufort Schools explicitly encouraged Szalai— who regularly contacted district officials with questions, suggestions on additional books to remove, and implications that it was not following the state’s process— to use the state-level process with any continued concerns. (It is hard not to project a feeling of frustration into the district’s responses, and easy to imagine that the district was hoping the State Board would be able to resolve the situation in a way that would tie up less district administrative time and resources.)

The Board has not set clear precedents for its bans.

When the Board considered 1984, the most similar book in content and themes to The Handmaid’s Tale which has been challenged so far, it did so without publicly reviewing the book’s language. Although the book does contain a significant number of “depictions of sexual conduct” under a plain reading of the regulation, the unnamed staff member who wrote the advisory review of 1984 for the Board’s Instructional Review Committee— no longer included on the committee’s official webpage— included no excerpts from the book.

The district challenge against The Handmaid’s Tale, however, like most or all of Szalai’s challenges, contains a long list of excerpts from the novel seemingly taken directly from BookLooks, the now-defunct Moms for Liberty-affiliated website frequently used in making book challenges throughout the country. (The Board itself is not required to read the books, and staff members, according to attorney Robert Cathcart’s remarks during committee hearings, only have to confirm that the books contain “depictions of sexual conduct”.)

Multiple speakers at the Board’s public hearings (including me) have argued that removing books like Flamer (which has no explicit depictions of sex) while retaining 1984 (which has many) is inconsistent at best and unconstitutional viewpoint discrimination at worst.

Many of Szalai’s BookLooks from The Handmaid’s Tale do contain “depictions of sexual conduct”. My reading of these is that they are only slightly more graphic than the many “depictions of sexual conduct” which appear in 1984, but, again, the Board did not show any public evidence of having read or even having considered excerpts from 1984. So while it might be consistent to retain The Handmaid’s Tale, defenders of the book can be reasonably concerned that the Board may ban it if it does come up for a formal challenge.

It also should be said that many of the groups and figures who have pushed school-level book bans have also spoke positively of 1984, perhaps viewing it (probably wrongly) through an anti-Communist lens (Orwell, for his part, was an avowed socialist who specifically opposed Stalinism, and some of the book’s most pointed criticisms are of the way the Party uses hypocritical restrictions of sexuality to channel the aggression of the population). But they have also spoken in favor of many of the ideals about traditional family, restrictive gender roles, and anti-feminism that The Handmaid’s Tale most clearly attacks.

So the best guess is that if the Board does take up The Handmaid’s Tale, it will end up removing it from every school in the state, while retaining 1984. If, on the other hand, Beaufort Schools is compelled to re-consider The Handmaid’s Tale under the current regulation, it will likely have to do the same for its own students, regardless of what its formal book review committees or the majority of its residents may prefer.

You can contact members of the South Carolina State Board of Education by using the emails listed here. If you receive any responses, I would love to hear about them!

Ways to support this work:

Here I should point out the significant recent criticism of Atwood’s treatment of racial minorities in the novel. For example, culture critic Angelica Jade Bastién wrote for Vulture in 2017, “In Atwood’s novel, black people are mentioned in only a few sentences to alert readers that they’ve been rounded up and sent to some colony in the Midwest, in a move that resembles South Africa’s apartheid. This decision feels like the mark of a writer unable to reckon with how race would compound the horrors of a hyper-Evangelical-ruled culture. Furthermore, it misrepresents how black and brown people resist in times of crisis. As writer Mikki Kendall noted on Twitter, ‘black people did not survive slavery, Jim Crow, and the war on drugs to be taken out by a handful of white boys with guns.’”

Further Reading:

"Protecting" children

This writing and research are possible because of paid subscribers. Please consider a subscription or donation.

South Carolina Becomes the Nation's Top Book Banner

This piece has been updated to include further excerpts from public comment and additional information.

[Historically] Banned Book #3: WE, by Yevgeny Zamyatin

I’m working on a series of pieces on significant banned/ challenged books. I also wrote about Jason Reynolds’ Stamped and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist. I plan to continue with books that are either being banned/ challenged today, or add more to the historical/ literary context of movements to ban books and ideas.

![[Historically] Banned Book #3: WE, by Yevgeny Zamyatin](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Phlq!,w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb187041d-664a-44c8-a274-9f5a1fd5801f_483x600.jpeg)