[Historically] Banned Book #3: WE, by Yevgeny Zamyatin

What can we learn from a century-old Russian sci-fi novel?

I’m working on a series of pieces on significant banned/ challenged books. I also wrote about Jason Reynolds’ Stamped and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to be an Antiracist. I plan to continue with books that are either being banned/ challenged today, or add more to the historical/ literary context of movements to ban books and ideas.

Continued attacks on Zamyatin throughout the twenties by Communist critics who had no taste for his “pernicious” ideology culminated in a defamatory campaign which ostracized him from Soviet literature in the autumn of 1929.

-Alex M. Shane, introduction to A Soviet Heretic (1970)

I am afraid we shall have no genuine literature until we cease to regard the Russian demos as a child whose innocence must be protected.

-Yevgeny Zamyatin, “I Am Afraid” (1921)

He loved jokes and caricatures, but never about himself.

-Stephen Kotkin, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power (Volume 2)

To paraphrase a popular SNL character, this book has it all: dystopian science fiction satire, bizarre mathematical metaphors, double-crossing, triple-crossing, perhaps even quadruple-crossing, love triangles, love quadrilaterals, love hexagons, weird technology, Freudian dream imagery, Russian futurism, Dostoevsky references, Frederick Winslow Taylor…

By many accounts, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 novel WE is the first modern futuristic dystopian novel. George Orwell noted WE’s similarities to the later novel Brave New World, and many critics believe it provided the basis for Orwell’s own novel 1984, perhaps the most influential and well-known Western dystopian novel ever written.

Orwell, who published 1984 in 1949, summarized WE this way in 1946:

In the twenty-sixth century, in Zamyatin’s vision of it, the inhabitants of Utopia have so completely lost their individuality as to be known only by numbers. They live in glass houses (this was written before television was invented), which enables the political police, known as the ‘Guardians,’ to supervise them more easily. They all wear identical uniforms, and a human being is commonly referred to either as ‘a number’ or ‘a unif’ (uniform)1. They live on synthetic food, and their usual recreation is to march in fours while the anthem of the Single State is played through loudspeakers. At stated intervals they are allowed for one hour (known as ‘the sex hour’2) to lower the curtains round their glass apartments. There is, of course, no marriage, though sex life does not appear to be completely promiscuous. For purposes of love-making everyone has a sort of ration book of pink tickets, and the partner with whom he spends one of his allotted sex hours signs the counterfoil. The Single State is ruled over by a personage known as The Benefactor, who is annually re-elected by the entire population, the vote being always unanimous. The guiding principle of the State is that happiness and freedom are incompatible3. In the Garden of Eden man was happy, but in his folly he demanded freedom and was driven out into the wilderness. Now the Single State has restored his happiness by removing his freedom.

That’s a fairly accurate summary, and strong evidence that 1984, which shares a similar plot and central ideas (constant surveillance, a central male character keeping a diary, a female foil who represents an alternative life, a twist ending, satire of existing authoritarian regimes) is based closely on WE. But it also obscures how weird and funny WE is, because it doesn’t really account for Zamyatin’s strange, meticulous, and intentional4 style.

There were “negative utopias” before WE, and probably before Utopia. Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1862) has often been called one of the first dystopian novels. Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1908) also predates WE.

But much of what contemporary audiences think of when they imagine “dystopian” literature (particularly after the great Young Adult Dystopia obsession of the early 21st century5— not that this kind of book has gone out of style with young readers), is probably much more like the society in WE— a polished, gleaming, mechanized, clean, and utterly banal surface masking a terrifying loss of humanity— than the society of 1984, with its clear analogs to Post-WWII London: bombed-out buildings, rationing, rats, etc.

I think the general consensus in the West is that Orwell’s book is better (and in some ways Orwell thought Brave New World, which also bears striking similarities to WE, was better). Although it’s not that interesting to pit works of art against one another in competition, much of WE’s power comes from repeat readings, and from the way its stylized and intentionally absurd future makes it perhaps both more timeless and more of a clear window into the specific ideological fascinations of the early 1900s, whereas the power of Orwell’s book is that it feels so plausible, especially in the aftermath of WWII. WE feels like an allegory for a problem that may be endemic to all societies; Orwell’s feels tied to a physical reality.

For me, the intentional absurdity and ridiculousness of Zamyatin’s style in the novel, like that of his contemporary Kafka, make the darker takeaways of the book somehow more disturbing, while also being more fun to read. In this way, the book might be more similar to the fable-like Animal Farm. The style and weird humor can lull the reader into a sense of abstraction, but this is revealed by the end of the book to be the same trick the state has played on its citizens: the ridiculousness hides the human cruelty of totalitarianism, state executions, disinformation, censorship, and dehumanization. For all its gleaming surfaces, the people in WE essentially live in what the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham termed a panopticon— a prison where the inmates know they are being constantly watched, and where the one hour a day of privacy exists to create an illusion— or what the philosopher Jean Baudrillard called a simulacrum— of a form of life that doesn’t exist. (If you only have an hour so that your unseen jailor can convince you that you’re not in a prison, it could be argued that you are the ultimate prisoner.)

D-503 calls this “our mathematically perfect life” (4) on the second page of his journal, and what could be more similar to the dream of tech bros and data-obsessed Taylorists today? (Taking this a step further, there is a darkly hilarious sequence in which “a dozen ciphers” are burned up when the engine of the spaceship whose construction D-503 is supervising accidentally fires, and the narrator can only express “pride” that the survivors never falter in their work. In 2021, future X-owner and tech bro par excellence Elon Musk famously said, about future missions to Mars, “Honestly, a bunch of people will probably die in the beginning”.6

And while many in the West have given in to the temptation to read Zamyatin— like Orwell— as simplistically “anti-Communism” or “anti-socialism,” there isn’t really any reason to believe that Zamyatin didn’t support at least the initial goals of the Marxist revolution in Russia. And much of his scorn in the novel isn’t for socialist utopian ideas, but in the ways in which they are carried out in an arguably “capitalist” fashion. Although there are many contemporary targets for his satire, the only one which gets called out by name is Frederick Winslow Taylor, and he gets called out by name a lot.

D-503 might best be described as a huge dork throughout most of the novel, and he is a total Taylor fanboy:

“Yes, that Taylor was, without doubt, the most brilliant of the Ancients. True, he didn’t think everything through, didn’t extend his method throughout life, to each step, around the clock. He wasn’t able to integrate his system from an hour into twenty-four. But all the same: how they could have written whole libraries about the likes of Kant— and not take notice of Taylor, a prophet, with the ability to see ten centuries ahead?” (31).

In a way, WE depicts the world after the last futile struggle for humanity represented in 1984 has already been lost. The protagonist, D-503, begins the book at least superficially accepting that everything in his society— translated as The One State in Natasha Randall’s translation7, but as the United State in some others— is as it should be. He is not the conflicted and tortured person Winston Smith is— at least at the beginning of the book8— and one struggle many readers might have with the book is that initially D-503 is not especially likeable or interesting, and because of his (perhaps only surface-level) cult-like acceptance of the dogma of The One State, he has no real inner life except the complex one implied by his own writing style. When the mysterious I-330 takes an interest in him, I wonder if we are supposed to be incredulous, and to immediately become suspicious of her motives, if one of the book’s many sick jokes is that D-503 is so boring and pompous that only a spy would pursue him.

One reason for the book’s current cultural relevance is that its author was a victim of multiple censorship campaigns (much more similar to Maoist “struggle sessions” than whatever James Lindsay and Moms 4 Liberty imagine is happening to them) and was convinced enough that he could not write in his native Russia that he essentially exiled himself to France at the beginning of Stalin’s reign9.

This fact has led some to assume that WE is an “anti-socialist” or “anti-Communist” novel, but this is a mistake of oversimplification: Zamyatin joined the Bolshevik Party and supported the revolution against the Tsar; he was a successful Bolshevik writer… until he wasn’t. As Randall writes in the introduction to her translation, it was the Party which slowly turned against Zamyatin, not the other way around: “As a writer, however, Zamyatin had been suspected of antipathy toward the Revolution and the Bolsheviks since his return to Russia in 1917. According to Alex M. Shane he was considered a bourgeois writer and an internal émigré” (xv). And while the book anticipates in many ways movements into totalitarianism, it was written just a few years into the Revolutionary period, and before Lenin’s death and Stalin’s rise to power.

This wasn’t the first time Zamyatin ran afoul of the Bolshevik government, either: according to Michael Brendan Dougherty, “Although he would go on to work for the regime's department of naval architecture, he wrote a fictional work, At the World's End, that was a satire of life in the military. He was acquitted in a trial over the book's seditious themes, but all copies of it were destroyed.”

In other words, Zamyatin wasn’t canceled by ideological enemies, but censored repeatedly because he failed political purity tests. And if his work seems prophetic now, that only demonstrates that he saw the writing on the wall, and the defenders of the current state dogma were too afraid to look at the uncomfortable truths he brought to light. What did Russia gain for this, except the chance to prove Zamyatin right when Stalinism ended up looking a lot like the One State’s rule: heavy on censorship and control of the arts and media, intolerant of any criticism of the Party, and willing to crush humanity— to the point of murderous purges against political enemies (a period in which Zamyatin very well might have faced death or imprisonment had he not asked Stalin to allow him to emigrate in 193110) and the starvation of millions— in pursuit of consolidated power and the mechanization and collectivization of a largely agrarian country.

Yet Zamyatin’s book isn’t about Stalinism specifically— it was written before Lenin’s death, in the early years of post-revolutionary Russia— and therefore the questions it raises should be posed by any society that values balancing progress and individual freedom with state power and reforms.

Similarly, Orwell was a passionate anti-Stalinist and also a self-described socialist. If Zamyatin were more popular— or more widely taught in the US— perhaps he would face the same weird contradictions as 1984, which has been “challenged for its pro-communist and sexually explicit content” while also being lazily and repeatedly embraced by a certain brand of conservative as a way to complain about being “canceled” for doing things like inciting violence. Orwell, like Zamyatin, was concerned with the way language and surveillance can be used to twist reality through disinformation until individuals cannot decipher reality from truth, until people willingly live in a prison without accepting that it is a prison.

Zamyatin new about state power and it’s potential dangers: he was exiled by the Tsar’s government for his membership in the Bolshevik party, and was exiled a second time after sneaking back into St. Petersburg to live secretly and write. In 1919 and 1922, he was imprisoned again— by his own party, the Bolsheviks. According to Alex M. Shane’s introduction to A Soviet Heretic, a collection of Zamyatin’s essays on literature, philosophy, and the craft of writing,

His emphasis on the role of the writer’s unconscious was decried as ‘false and pernicious bourgeois ideology’ by Soviet critics and was subjected to violent criticism in 1931 during the extensive discussions of creative method in writing…

There are a lot of surface-level similarities between our era and D-503’s. D-503 lives in a surveillance state, thanks to a futuristic glass that makes up every building and allows police spies (“Guardians”)— and everyone else— to observe “ciphers” virtually constantly. His government attempts to solve its problems by creating a giant wall around the city. His society is obsessed with Taylorism to the point that it schedules every aspect of life (something clearly inspired by the train schedule of Zamyatin’s era, but much more similar to the way contemporary societies run their businesses, schools and other institutions).

But beneath those, the central problem Zamyatin seems to be satirizing is the way in which powerful groups ultimately gain control not through physical violence but through soft power— censorship, propaganda, disinformation, and a kind of state religion (in which people worship a human Benefactor— or maybe a series of interchangeable Benefactors, depending on how you interpret the book’s in-universe history— as if he is an immortal god) tailor-made to achieve the goals of the powerful. It’s not clear whether the One State was started with a malicious intent or if, as it claims, it was making a good faith effort to save humanity from a repeat of the Two Hundred Years War, which supposedly destroyed almost every human being on the planet.

As Margaret Atwood (no stranger to censorship herself) writes in her forward to Bela Shayevich’s 2020 translation,

In his 1921 essay “I Am Afraid,” Zamyatin said: “True literature can exist only when it is created, not by diligent and reliable officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels, and skeptics.” In this he was a child of the Romantic movement, as was the Revolution itself. But the “diligent and reliable officials,” having seen which way the Leninist-Stalinist wind was blowing, were already busying themselves with censorship, issuing decrees about preferable subjects and styles, pulling out the unorthodox weeds. This is always a dangerous exercise in totalitarianism, since weeds and flowers are likely to change places in the blink of an eye.”

This is where WE and 1984 share the most DNA: this fear of a kind of rewriting of reality (what some have called “post-truth”) through censorship and the deliberate manufacture of confusion and distrust, through disinformation, to destabilize the ability of the public to engage in meaningful debates or discussions, to hold their leaders accountable, and to work together to solve social problems.

Zamyatin, for his part, didn’t seem to think there was a solution to these problems; the goal of an artist wasn’t to offer a fix, but to bear witness to the ongoing revolution, to push art forward, to force it to evolve, to evolve with it. As he wrote in the essay, “Literature, Revolution, Entropy” (1923), shortly after initially trying to publish WE in Russia (he even includes an epigraph from WE at the top of his own essay):

The flame will cool tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow (in the Book of Genesis days are equal to years, ages). But someone must see this already today, and speak heretically today about tomorrow. Heretics are the only (bitter) remedy against the entropy of human thought (108).

The enemy of the heretic, Zamyatin continued, is “dogma”. And speaking more directly to the paradox of censorship, he wrote, in the same essay,

It is just to chop off the head of a heretical literature which challenges dogma; this literature is harmful.

But harmful literature is more useful than useful literature, for it is antientropic, it is a means of combatting calcification, sclerosis, crust, moss, quiescence. It is utopian, absurd… (109).

WE satirizes many things— Taylorism perhaps most directly— but the real terror in its satire is the terror of a world that crushes truthtellers, that requires conformity as a way of protecting itself from change, which of course makes it incapable of reacting to change. One of the many subversive elements of the book is that its narrator— the nominal protagonist— takes almost no action that isn’t at least consciously aimed at avoiding change. His central conflict throughout the book is an internal one: a kind of weak game where he (pretends?) to struggle to turn himself into the police (in a possible parody of Crime and Punishment). It is I-330, his lover— who is perhaps merely exploiting him in a kind of honeypot spy game, but this is never really confirmed— who acts more like a protagonist. She is the heretic, the one Zamyatin quotes at the top of his essay saying “Revolutions are infinite,” the one who seems to have much more to do with the book’s movement into its climax.

And it seems clear that the author saw both the danger and power of satire very clearly11. As the book reaches its climax, D-503 realizes “laughter is the most terrible weapon: you can kill anything with laughter” (184). One of the more sympathetic characters in the book, a woman D-503 only calls “U,” reports her students to the secret police because they draw a caricature of her looking like a fish. Laughter reduces power that comes from mystique, and Zamyatin was brave or foolish enough to puncture the mystique of those in power; for this, his career was destroyed and he might have very well lost his life if things had gone slightly differently.

These issues are more relevant than ever in our era. Zamyatin, writing in a time in which international mass media was only starting to come into being, could already see the danger of a group— in the case of WE, the state— monopolizing truth. In the era of social media, the danger becomes that many groups can monopolize many truths, using algorithms and targeted marketing and technology that weaponizes human psychology to feed each bubble the perfect lie, all while constantly surveilling them for more data to get better at it. While Zamyatin’s “ciphers” are metaphorically imprisoned in literal glass apartments, and literally imprisoned within a literal glass wall, modern readers are increasingly imprisoned in a metaphorical glass box, but the glass tends to be one-way.

And, as in Zamyatin’s time, the propaganda of our era masterfully confuses the issue. In my state of South Carolina, a group called the “Freedom Caucus” has just declared war on the American Library Association across multiple states, through statements would read like a parody of McCarthy-era Red Scare bullshit… except that they’re real. In the South Carolina statement, the authors write,

Ms. Dabrinski is a self-proclaimed Marxist who does not reflect the values of citizens across the Palmetto State… With parents facing ongoing issues regarding Un-American and inappropriate materials being foisted on their children through both school libraries and public libraries, Mrs. Dabrinski’s election is disturbing for the citizens we serve.

(Yes, they capitalize “Un-American”; yes, they claim that a book being in a library is equivalent to “foisting” it on a child; yes, the rest of the statement is equally silly, and yes, this is a group of elected state officials— officials who have already used state power to bully and censor libraries and school districts in South Carolina for not adhering to their preferred orthodoxy— arguing that a nonprofit group that represents libraries and encourages literacy should fire an elected member because she’s in the wrong political party.)

The statement, like so many in recent years, reminds me forcefully of one of the One States’ “articles” in the State Gazette (Zamyatin was eerily accurate in imagining what a media ecosystem in which the state has a monopoly looks like). This one comes about mid-way through the book, when a pro-democratic act of rebellion (it involves people voting!) has threatened to upend the entire crystalline structure of the society.

YESTERDAY, THE LONG AND IMPATIENTLY AWAITED DAY OF THE ONE VOTE TOOK PLACE. FOR THE 48TH TIME THE BENEFACTOR, WHO HAS PROVEN HIS UNSHAKABLE WISDOM MANY TIMES OVER, WAS UNANIMOUSLY CHOSEN. THE CELEBRATION WAS CLOUDED BY A SLIGHT DISTURBANCE WROUGHT BY THE ENEMIES OF HAPPINESS, WHICH, NATURALLY, DEPRIVES THEM OF THE RIGHT TO BECOME BRICKS IN THE FOUNDATION OF THE ONE STATE, RENEWED YESTERDAY. IT IS CLEAR TO EACH OF US THAT TAKING THEIR VOICE INTO ACCOUNT WOULD BE AS RIDICULOUS AS TAKING THE ACCIDENTAL COUGHS OF SICK PEOPLE IN A CONCERT AUDIENCE AS A PART OF A MAJESTIC, HEROIC SYMPHONY…

The logic is disturbingly parallel: Your vote only counts if you vote the way the state wants you to vote, and for the “Freedom Caucus,” your views, politics, and identity are only protected by the First Amendment if you have the right kind of views, politics, and identity.

Similarly, groups like Moms for Liberty engage in Orwellian/ Zamyatinian self-parody when they proclaim “educational freedom” but ally with the state to choose which ideas and texts are acceptable for everyone. And in comparing peaceful criticism of their efforts by fellow citizens with “struggle sessions,” they (probably intentionally) misrepresent and misread the lessons of historical totalitarian societies like the one Zamyatin seemed to fear would develop in his own country, if “heretics” who were unafraid to speak truth to power were prevented from being able to do so.

For anyone interested in discussing, teaching, studying, or conducting a book club for WE, I’ll share some of the materials I developed while teaching the book for the past ten years, in this folder. (Tragically, many materials were lost when my old district deleted my account.)

Here’s my version of a teacher supply list:

I’m currently looking for my next full-time job, and supplementing my income through writing, including this newsletter. If you found this useful or interesting, please help me continue this work by sharing and/ or subscribing. Every little bit helps.

In Natasha Randall’s translation, the word for people living in the One State is “cipher,” which is a choice that fits well with Zamyatin’s compressed and frequently math-inspired style; a “cipher” can be a person who is hard to read, a mathematical code, a zero, or the process of doing math. To “decipher” is to make something which is encoded plain.

Randall’s translation calls this time the “Personal Hour” and her narrator, D-503, dreams of the day when the One State will get rid of this last vestige of humanity, too. While I have never experienced a challenge against WE, if it ever does get challenged it will probably be on the silly basis that it has the word “sex” in it a handful of times. There are no explicit sex acts described in the book, though there are some fairly G-rated scenes suggesting that D-503 has taken separate “personal hours” with two of the points on his love hexagon. For comparison, Shakespeare gets in much more bawdy material in the first few scenes of Romeo and Juliet. But one of the features of the great book ban craze of the last few years is creating an arbitrary metric of “inappropriateness” and applying it selectively to any books that don’t pass ideological muster; I assume Zamyatin’s Tsarist and Bolshevik censors would approve.

D-503’s friend R-13, a poet (of course!) uses the Biblical story of Adam and Eve as an allegory for the One State: “Those two in paradise stood before a choice: happiness without freedom or freedom without happiness; a third choice wasn’t given” (55). Arguably, WE is a novel about the difficulty and potential rewards of breaking out of this binary, of choosing a different freedom that allows for happiness.

Style is very important to Zamyatin. In his essay “I Am Afraid,” he complains that “all of the practitioners of proletarian culture have the most revolutionary content and the most reactionary form” (56). In “Literature, Revolution, Entropy,” he writes, “The old, slow, creaking descriptions are a thing of the past; today the rule is brevity— but every word must be supercharged, high voltage… And hence, syntax becomes elliptic, volatile; the complex pyramids of periods are dismantled stone by stone into independent sentences…. The image is sharp, synthetic, with a single salient feature— the one you will glimpse from a speeding car”. (All quotes from these two essays come from Mirra Ginsburg’s translations in A Soviet Heretic: Essays by Yevgeny Zamyatin, Northwestern University Press, 1970.)

Some texts that have been very popular with my students over the years: Feed (Anderson), the Hunger Games Series (Collins), the Divergent series (Roth), The Giver (Lowry). The primary reason I have taught WE so long is that I started using it with a unit on dystopian literature in a world literature course, and kids seemed to get into it. (Not at first; it’s a deeply weird book, and teenagers tend to need to know they are in on the joke before they trust a book. By the end, they’re usually hooked. See also: Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”.)

I wonder if Musk, a hard sci-fi fan, has read the novel. From a recent New Yorker piece about the hold Musk has over governments reliant on his technology: “Even Musk’s critics concede that his tendency to push against constraints has helped catalyze SpaceX’s success. A number of officials suggested to me that, despite the tensions related to the company, it has made government bureaucracies nimbler. ‘When SpaceX and nasa work together, we work closer to optimal speed,’ Kenneth Bowersox, nasa’s associate administrator for space operations, told me. Still, some figures in the aerospace world, even ones who think that Musk’s rockets are basically safe, fear that concentrating so much power in private companies, with so few restraints, invites tragedy. ‘At some point, with new competitors emerging, progress will be thwarted when there’s an accident, and people won’t be confident in the capabilities commercial companies have,’ Bridenstine said. ‘I mean, we just saw this submersible going down to visit the Titanic implode. I think we have to think about the non-regulatory environment as sometimes hurting the industry more than the regulatory environment.’”

Randall’s translation is my favorite (although that may be in part because I read it first). I think part of what makes her an ideal translator is that she is a trained physicist, and Zamyatin’s mathematical language, which is essential to understanding both the larger ideas of the book and its rocket scientist narrator, is probably easy to miss for many translators and readers. “Literature, Revolution, Entropy” provides a great example of the importance of mathematics to Zamyatin’s philosophy: “Absurd? Yes. The intersection of parallel lines is also absurd. But it is absurd only in the canonic, plane geometry of Euclid. In non-Euclidean geometry it is an axiom. All you need is to cease to be plane, to rise above the plane. To literature today the plane surface of daily life is what the earth is to an airplane— a mere runway from which to take off…” (111).

Of course, one reason for this may be that Orwell’s narrator is writing in a secret journal, whereas Zamyatin’s is writing his— at least, at first— with the intention of handing it over to the One State for use in the propaganda spaceship: “This text is me; and simultaneously not me. And it will feed for many months on my sap, my blood, and then, in anguish, it will be ripped from my self and placed at the foot of the One State” (4). One thing that’s fascinating about this very early entry in D-503’s journal is that while D-503 says he embraces the “mathematically perfect,” logical life of the One State, he writes with the fiery passion of a poet or a “heretic”.

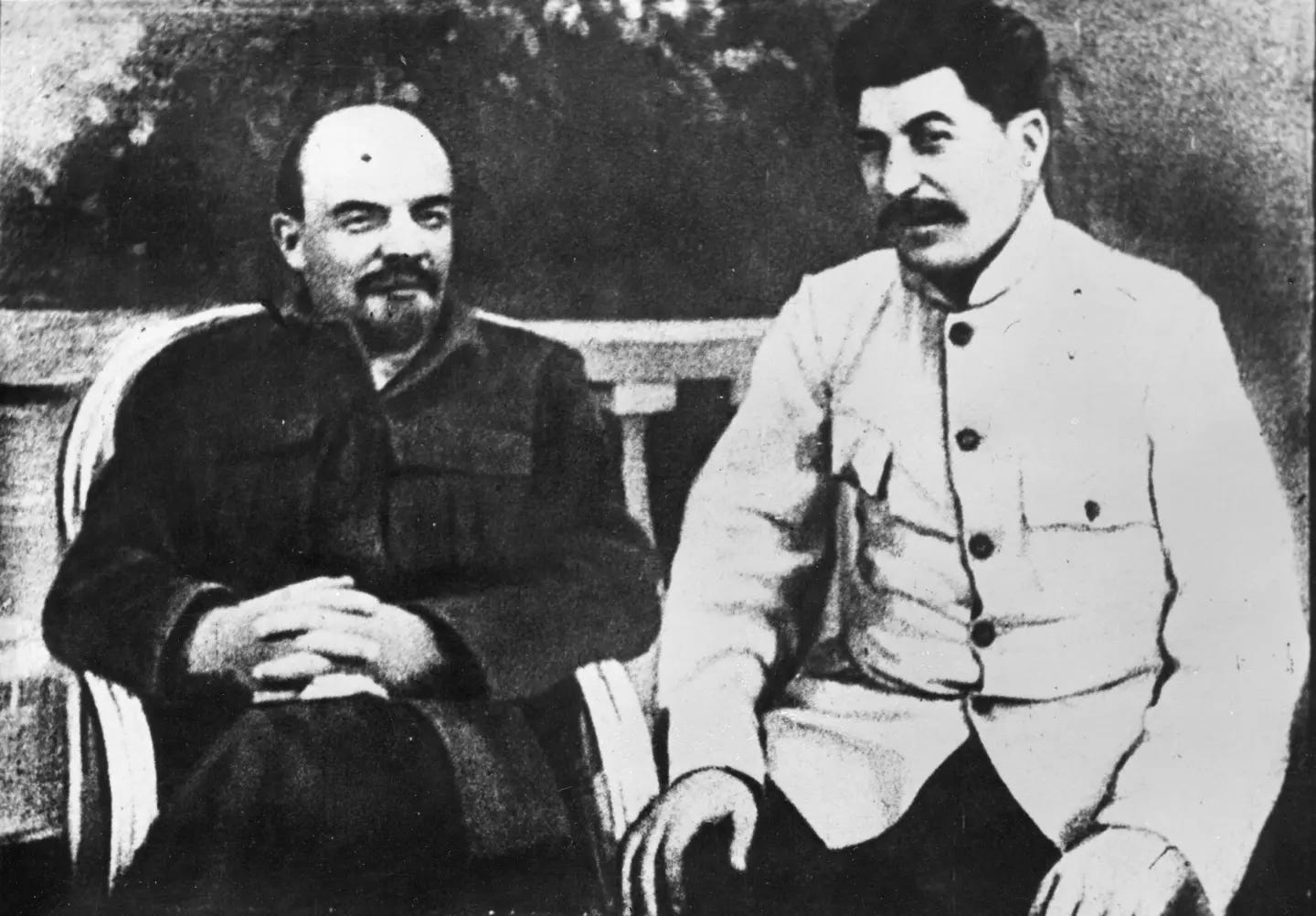

One of the many frightening ironies of Stalin’s reign is that Stalin, himself, had also spent his youth reading books banned by the Tsarist government, and was placed under surveillance by the government after starting an illegal book club and becoming involved in protests (Kotkin, Stalin: Paradoxes of Power Volume 1, p. 49). Young Stalin was inspired by “questioning the socialist establishment” and writing against “a diluted Marxism” (48). Young Stalin seems to have had a lot in common with Zamyatin; according to Kotkin, many critics have missed the role of dictatorship, itself, in turning Stalin into what he would later become.

In his letter to Stalin, Zamyatin described the censorship of his works as a “literary death”. For whatever reason— perhaps because of Zamyatin’s relationship with Maxim Gorky— Stalin allowed Zamyatin to leave Russia before the Great Purge began around 1936.

I often wonder if what really got Zamyatin in trouble is a passage where (major spoiler) D-503 meets the Benefactor in person, towards the end of the novel. At first, the One State’s control of reality is so powerful that D-503 still sees a massive figure with “cast iron hands” (186). But then, after some conversation: “I remember very clearly: I started to laugh and lifted me eyes. Before me sat a bald, Socratic-bald person, and there were fine droplets of sweat on his baldness.” It is as if a spell is lifted, and D-503 sees that the Benefactor is a normal mortal, and that by extension his belief in the One State’s perfection is absurd. Perhaps knowing this, Stalin had photographs of himself airbrushed to remove his pock marks and was self-conscious about a hand injured by childhood polio. An idea is hard to defeat; a human being is not.

Stalin and Lenin in 1922: