Other Duties as Assigned, Part II

SC teacher contract law, school funding, and teacher retention in the pandemic era

Note: This post is Part II in a series. Part I can be read here. Part III can be read here.

BOATSWAIN What cares these roarers for the name of king? To cabin: silence! trouble us not.

GONZALO Good, yet remember whom thou hast aboard.

BOATSWAIN None that I more love than myself.

-The Tempest, Act I, Scene I, William Shakespeare

As discussed in Part I, school districts are in a bind when it comes to teacher retention: the state legislature, while it has provided little in the way of carrots for districts to offer educators, has offered instead one fairly cruel and clumsy stick— the threat of the revocation of a teacher’s license for the crime of seeking to break an objectively one-sided contract.

In better times, the fear of losing that credential was very real for many educators, because better-staffed schools meant fewer job openings, and benefits and salaries compared more favorably with the private sector, making teachers and school staff more reluctant to leave schools. A few years ago, a district superintendent even told me he didn’t think there would be significant retention problems created by the then-looming pandemic, because now more than ever teachers would need their health insurance.

Obviously, he was wrong, for reasons I covered a little bit last week, when I explained that I am not a robot. I think the articles and think pieces about how easy it is for teachers to switch professions right now are somewhat overstated (at least in terms of South Carolina, where I live), but it is clear that there are more jobs out there for teachers than there were a few years ago. Teachers, after all, tend to have advanced degrees, experience managing people and handling stress, and public-facing skills. Now more than ever I am hearing from teachers and seeing posts on social media wondering, What’s next? How do I leave this job.

A few weeks ago, I got in contact with attorney Grant Burnette LeFever, Esq., with Burnette Shutt & McDaniel, PA. She was kind enough to answer some questions that got a little more in-depth in terms of SC teacher contract law.

Of course, if you are contemplating breaking, challenging, or negotiating a contract you should consider consulting directly with an attorney, and LeFever’s comments are intended for purely informational purposes, and not as legal advice.

One of the central questions teachers in South Carolina face is, are there legal limits to the “other duties as assigned” language in South Carolina teacher contracts and job descriptions?

Here is what LeFever had to say:

The Fair Labor Standards Act specifically exempts teachers from its minimum wage and overtime requirements when they perform extra duties at their schools in support of extracurricular activities. Here is the exact language of the regulation that touches on these “other duties”: “Those faculty members who are engaged as teachers but also spend a considerable amount of their time in extracurricular activities such as coaching athletic teams or acting as moderators or advisors in such areas as drama, speech, debate or journalism are engaged in teaching. Such activities are a recognized part of the schools' responsibility in contributing to the educational development of the student.” 29 C.F.R. § 541.303(b). I am not aware of any case law or guidance on the issue, but I think the last sentence arguably could be read to limit a teacher’s extra duties to those that are “a recognized part of the schools’ responsibility in contributing to the educational development of the student.” However, this is very open language, and I think the courts likely would afford broad discretion to districts in determining qualifying and non-qualifying duties.

That said, if the “other duties” assigned were so numerous and of such a nature that the employee’s “primary duty” no longer could be considered “teaching, tutoring, instructing or lecturing in the activity of imparting knowledge,” then that employee may not qualify for the FLSA teacher exemption and thus be entitled to a minimum hourly wage and overtime pay.

Beyond these two potential FLSA arguments, I am not aware of any established or reasonable expectations that limit the kinds of duties districts could assign.

In this context, “exempt from overtime” is federal law’s nice way of saying that it’s legal to require some people to work beyond “normal” work hours without paying them for the extra work.

What stands out here is the idea that the thing that makes a teacher a teacher, under the Fair Labor Standards Act, is the primary duty of “teaching, tutoring, instructing or lecturing in the activity of imparting knowledge”. Teachers seeking to push back on excessive and burdensome requirements might want to focus first on those tasks furthest from the reasonable job duties of a teacher. LeFever thought the arguments she outlined could also play into the case against Cherokee Schools, which I touched on more in Part I. (This makes sense to me. For example, the teacher in the Cherokee case was being required to run a concession stand. It’s hard to argue that is a part of the job of “imparting knowledge,” unless the goal is to model for students how to be exploited at work.)

I also asked LeFever whether the vagueness of the teacher contract language had any impact on how binding it might be. While she didn’t think the vague language itself presented a problem for districts under South Carolina law, she did point out that “under the South Carolina Payment of Wages Act, an employer must notify of employees at time of hire of their normal hours, wages agreed upon, time and place of payment, and deductions to be made.”

While districts seem to have a lot of flexibility in changing employee work schedules and duties, obviously districts are not following the spirit of the “wages agreed upon” requirement of Payment of Wages Act when they make reductions in salary after a teacher has signed their contract, as nearly every district did during the 2020-21 year, when South Carolina lawmakers froze teacher salaries.

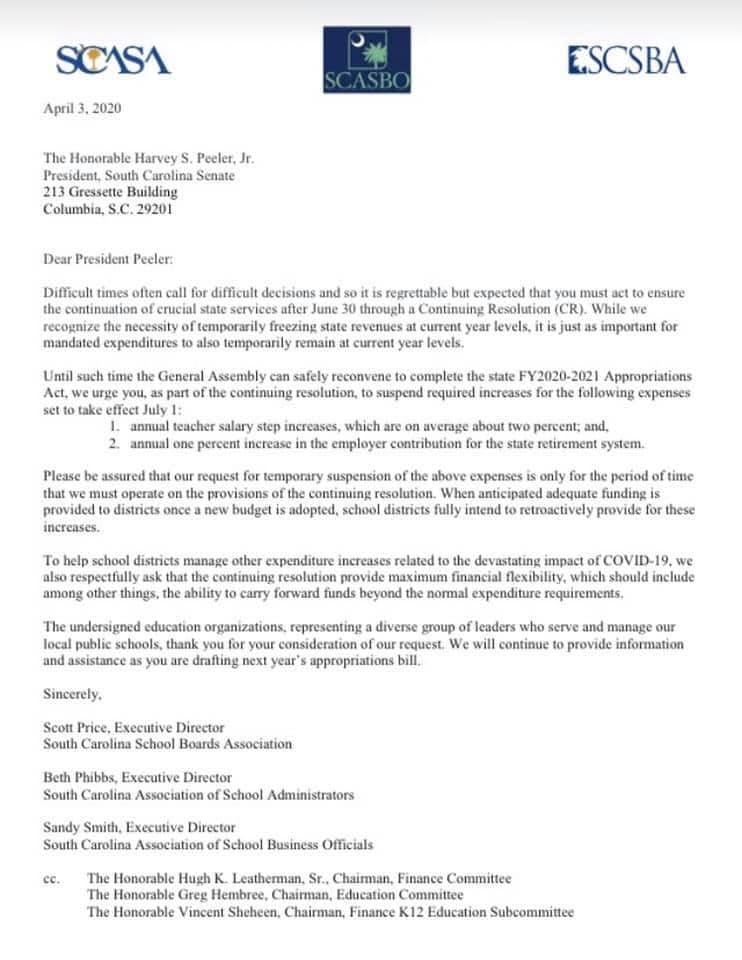

The freeze was at least partly on the advice of SCSBA (the South Carolina School Boards Association), SCASA (the South Carolina Association of School Administrators) and SCASBO (the South Carolina Association of School Business Officials). I’ve never completely understood the thinking of those organizations; while they claimed they were concerned that the pandemic would slash state and local budgets so much that they wouldn’t be able pay the state’s minimum required teacher salary, their gloomy economic predictions ended up being hilariously wrong. Currently, the state is sitting on billions in surplus budget dollars, including $1 billion in recurring funds. (Even as we ended the year of frozen salaries, the state already had a $1 billion surplus. To say that many teachers felt that getting a pay cut while suffering through a tumultuous year of pandemic horrors and remote and hybrid teaching was a slap in the face would be a major understatement.)

Whatever the reasons for the salary freeze, teachers all over the state signed a contract in May of 2020 expecting a specific salary (namely, the salary step beyond each teacher’s 2019-20 salary step) and were asked to just go with it when they returned in August of 2020 to a lower-than-expected salary and significantly different and more difficult job duties, which generally included remote and hybrid teaching, cleaning and sanitizing classrooms, offering tech support to students and families, and creating mountains of send-home work that would be unnecessary in a normal school year.

There is also a valid argument to be made that the state was already making it more difficult every year for districts to keep their promises to teachers concerning salary, even before the pandemic. While the legislature doesn’t explicitly freeze salaries every year, it does underfund Base Student Cost every year (a cumulative underfunding of schools that has added up to over $4 billion in the last decade alone) and this contributes to the fact that average teacher salaries for each year do not meet the southeastern average as required by law.

The Education Finance Act (Title 59, Chapter 20 of SC law) requires the following:

The state minimum salary schedule must be based on the state minimum salary schedule index in effect as of July 1, 1984. In Fiscal Year 1985, the 1.000 figure in the index is $14,172. (This figure is based on a 10.27% increase pursuant to the South Carolina Education Improvement Act of 1984.) Beginning with Fiscal Year 1986, the 1.000 figure in the index must be adjusted on a schedule to stay at the southeastern average as projected by the Office of Research and Statistic of the Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office and provided to the General Assembly during their deliberations on the annual appropriations bill. The southeastern average teacher salary is the average of the average teachers' salaries of the southeastern states. In projecting the southeastern average, the office shall include in the South Carolina base teacher salary all local teacher supplements and all incentive pay.

What this means is that each year the Office of Revenue and Fiscal Affairs calculates a new southeastern average teacher salary based on data from other states, and projects what the General Assembly’s funding goal should be for the average teacher salary in the state (including, crucially, local funding). Basically, the legislature required itself, in writing the Act, to make up the difference between what local districts could contribute and what teachers needed to make to bring the state average teacher salary to the southeastern average, in order to allow us to compete for teachers with our neighbors in other southeastern states.

There are probably many ways to achieve this southeastern average salary, including the most obvious: raise salaries for all teachers, and do more to retain veteran teachers, who generally make the highest salaries and thus bring up the average. A great way to achieve the second goal would be to add more steps to the state minimum salary schedule, which currently ends at Year 23, creating a significant wage penalty for our most experienced teachers (imagine, if you aren’t a veteran teacher, putting in over two decades of service and knowing the state will never guarantee you another cost of living adjustment). S. 317 would add five more steps to the schedule, which is at least a start, but would need significant pressure from voters to have any chance. (For the record, I don’t know if the southeastern average is a great target when we lose teachers to every state. The national average teacher salary was around $64,000 as of two years ago and is probably higher now).

But all of these steps are difficult, because the SC General Assembly, as it does with class size caps and anything else the state doesn’t want to fund, uses budget provisos to reduce funding below the minimum each year.

Salaries aren’t the only broken promise: teachers signed a contract in May 2021 to teach, only to return to a situation in which many had become unpaid classroom monitors during their planning time, as well, as I discussed in Part I. I still think there is an argument to be made that babysitting classes because districts can’t get enough subs is not a part of a teacher’s FMLA-defined job, and should be compensated as extra work. (Obviously, most districts also need to recognize the valuable contributions of substitute teachers and pay them significantly more.)

Many teachers this year also retained the new job duties of creating virtual lessons (and sometimes teaching them to virtual students while simultaneously teaching in-person students, something the legislature tried to limit, but which seemed to be happening a lot, nonetheless). Even when the legislature passed a law requiring that teachers be compensated for some of these “other duties as assigned” (the ones that involved virtual-and-in-person hybrid instruction) many districts evidently just didn’t pay up, which might have been illegal, though I’m not aware of any action that the state took. In a survey of about 1,600 school staff members conducted by SC for Ed in November 2021, over 600 had already been required to teach hybrid classes; only about half had been compensated.

Similarly, according to the same survey, 56% of school staff members were required to sub for absent teachers, but the majority of these staff members were not compensated for this extra work.

Whether or not what districts are doing is illegal— and language in the teacher contract is usually intended to protect them— I do think the idea that some of all of these duties should not be exempt from overtime is something worth exploring for teachers who might want to bring legal challenges.

That said, it seems that South Carolina law currently does little to protect teachers and other school staff from exploitation by districts (and certainly teachers are not alone in that: the state’s labor laws are notoriously tilted towards favoring employers). I think the best strategy for teachers who feel they are being tasked with excessive unpaid work (other than consulting directly with attorneys when possible) is to use our collective voice to push the General Assembly to pass laws creating a reasonable contract. For example, Senate Bill 348 and House Bill 3246 would remove the ability of districts to penalize teachers for simply seeking better work conditions or higher pay in another district. SC for Ed has forms you can use to contact your SC Senators and House members to support passage of these bills, neither of which seems to have had much action or interest, as the legislature spends its time trying to find ways to fund private school vouchers with public school money and promote boilerplate legislation intended to restrict what students can learn and discuss. You can also use the SC for Ed link to find out more about S.348/ H. 3246, which I discussed in Part I, and which would eliminate the ability of districts to challenge a teacher’s certification simply for seeking a different job.

One thing you may want to explain to lawmakers is that education is currently experiencing a sea change. The old tactics of controlling teachers weren’t working well before the pandemic (just look at these pre-pandemic turnover rates), but at that point I think teachers were still largely focused on changing the system proactively. Throughout the country and in SC, grassroots teacher movements flooded statehouses (as over 10,000 education supporters did on May 1, 2019 in SC), called strikes and walkouts (where strikes and walkouts were possible, and notably not in South Carolina) and captured the public attention.

In the pandemic era, many teachers seem to be walking away from the profession, instead, often for good. Unable to save what many see as a sinking ship, and unable to persuade leaders to act in the best interests of the state and its children, they feel they have no choice but to save themselves. In South Carolina and other states which have underfunded schools since the last recession, even the most generous proposals to increase teacher funding don’t address Base Student Cost, and come in the same session as sweeping proposals to censor and stifle teachers while redirecting potential billions in public funds to private schools. The ship is sinking, and we’re giving out money to build an alternative ship in the middle of the storm, while tearing apart the old ship for spite. (And in this metaphor, the bill sponsors couldn’t even agree to require this fabled alternative ship to take on the most vulnerable.)

Please call on our elected leaders to right the ship before it sinks.

Please consider supporting this work by subscribing for free and/ or upgrading to a paid subscription. Learn more about subscriptions by clicking here.

See similar content in much shorter chunks by following me on Twitter.