On Vacations and “Learning Loss”

This piece is available for free at the Center for Educator Wellness and Learning. (Click here to access it on CEWL’s website.)

Since the early days of the pandemic, pundits and researchers have fretted about “learning loss”. In practice, “learning loss” is really better described as a decrease of, or lack of improvement on, standardized test scores. Doubtless, someone somewhere is fretting about all of the learning that may evaporate from children’s heads over the winter holidays.

And there’s even a specific phrase used by testing companies for the “learning loss” that allegedly happens every summer vacation: “Summer slide” refers to the perception that students get worse at school over a long summer holiday. Early projections on the potential costs of virtual or hybrid schooling during the pandemic were often based on the assumption that we could map “summer slide” onto days of in-person school missed due to the pandemic.

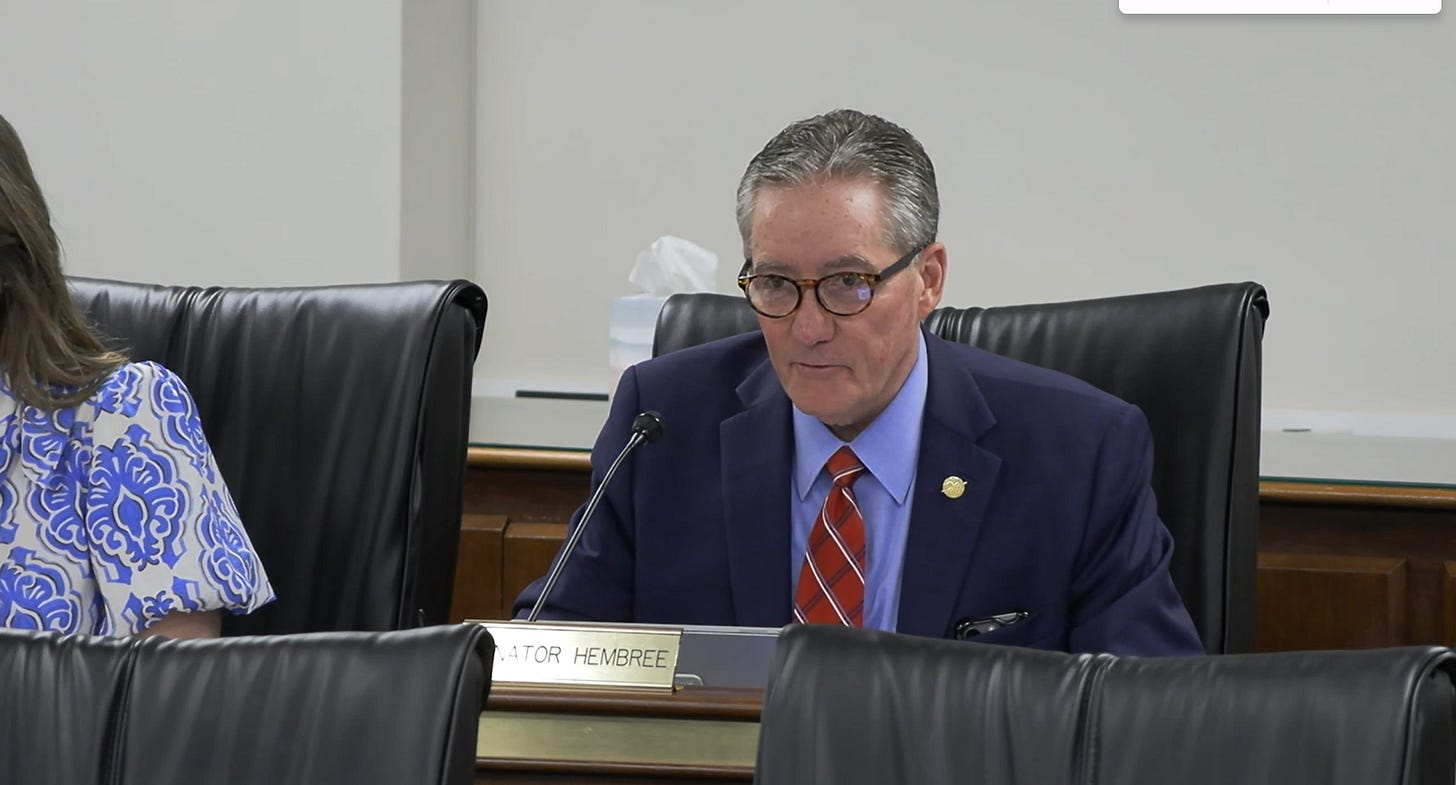

For example, in July 2020, SC Senate Education Chair Greg Hembree claimed that, “The data is telling us that in mathematics, on average, students have lost, not just that semester, but a complete year, and that in English, students have lost a complete semester.”

Hembree’s data came from an Education Oversight Committee report which actually contained no data about e-learning losses during the pandemic

Instead, it included two graphs from an article on EdNote, dated April 27, 2020, called “The Covid Slide and What It Could Mean for Student Achievement.” The provided graphs “forecast” nationwide learning loss due to COVID-19 based only on test scores for English and mathematics students in grades 3-8. The authors, rather than making claims about current learning loss, merely state, “Preliminary estimates suggest impacts may be larger in math than in reading and that students may return in fall 2020 with less than 50% of learning gains, and, in some grades, nearly a full year behind what NWEA would expect in normal conditions”

NWEA is the company that makes the MAP assessment. The company has a vested interest in promoting the idea that test scores consistently represent “learning”.

Hembree awarded the state’s teachers at the time “an A+ for effort” in teaching students, but a “D-” for “results”. But of course, this is was before we knew almost anything about the impact of the pandemic on “learning”; as questionable as test scores can be as proxies for what students have actually learned (and what they have learned to do), we didn’t even have those scores yet when Hembree and others were using this “projected learning loss” to argue for a return to in-person instruction.

Hembree’s extrapolation stretched the plausible limits of learning loss data in a way that unfortunately is all too common.

Learning loss alarmists often conflate test achievement and learning, which are, theoretically, closely related, but are objectively not the same thing. (It is possible for a student to score poorly on a standardized test even though they have mastered the content or skills the test is supposed to measure. It is possible for a student to be very good at taking standardized tests without learning the material.)

In other words, the test might be invalid. The student may perform poorly under stress. The student may fall asleep during the test. The student may be taking an electronic test on a broken computer. (Shortly after we did return to in-person learning, I watched a student take a state test on a Chromebook with a missing J key. As she was completing the essay component of the test, every time she needed to type J, she had to pick up a pencil and insert the tip of it into the keyboard.)

Secondly, like Hembree, the alarmists during and after the pandemic have conflated “summer slide”-style “learning loss” with an unprecedented situation that may or may not duplicate the conditions of being on summer vacation. (How similar is a global pandemic to a summer break?)

Of course, many students did face academic obstacles during the pandemic.

In particular students with fewer resources outside of school likely struggled the most.

Past research on “learning loss” addresses this:

“One commonly cited explanation for this phenomenon is a concept called the ‘faucet theory.’ This idea suggests that children attending the same school have relatively comparable resources available to them during the school year. However, during the summer, students from higher economic backgrounds continue to have access to materials and experiences that allow them to maintain higher rates of educational retention than their peers from resource-poor backgrounds. In other words, these children continue to have a running ‘faucet’ of resources even in the summer months—an advantage that students from lower socio-economic backgrounds lack.”

Indeed, leading up to the pandemic, South Carolina officials often heard from teachers who felt ongoing resource disparities between wealthier and poorer districts needed to be addressed in order to improve educational outcomes. These were central complaints in the May 1, 2019 rally in which 10,000 public education supporters marched on the SC capitol.

(Click here to access the full version of this article, for free, on CEWL’s website.)