What separates war from murder?

The thing that separates war from murder is the law…

Now, language is, among other things, a device which men use for suppressing and distorting the truth. Finding the reality of war too unpleasant to contemplate, we create a verbal alternative to that reality, parallel with it, but in quality quite different from it. That which we contemplate thenceforward is not that to which we react emotionally and upon which we pass our moral judgments, is not war as it is in fact, but the fiction of war as it exists in our pleasantly falsifying verbiage. Our stupidity in using inappropriate language turns out, on analysis, to be the most refined cunning.

— Aldous Huxley, “Words and Behavior”

“Human beings sent by the United States dropped explosives on other human beings in several locations in Venezuela during a 30 minute air attack this weekend, killing a currently unknown number of people on the ground.”

That may be how writer Aldous Huxley would have described the current media descriptions of what is happening in that country.

As he wrote in his 1936 essay, “Words and Behavior,”

“You cannot have international justice, unless you are prepared to impose it by force.” Translated, this becomes: “You cannot have international justice unless you are prepared, with a view to imposing a just settlement, to drop thermite, high explosives and vesicants upon the inhabitants of foreign cities and to have thermite, high explosives and vesicants dropped in return upon the inhabitants of your cities.”

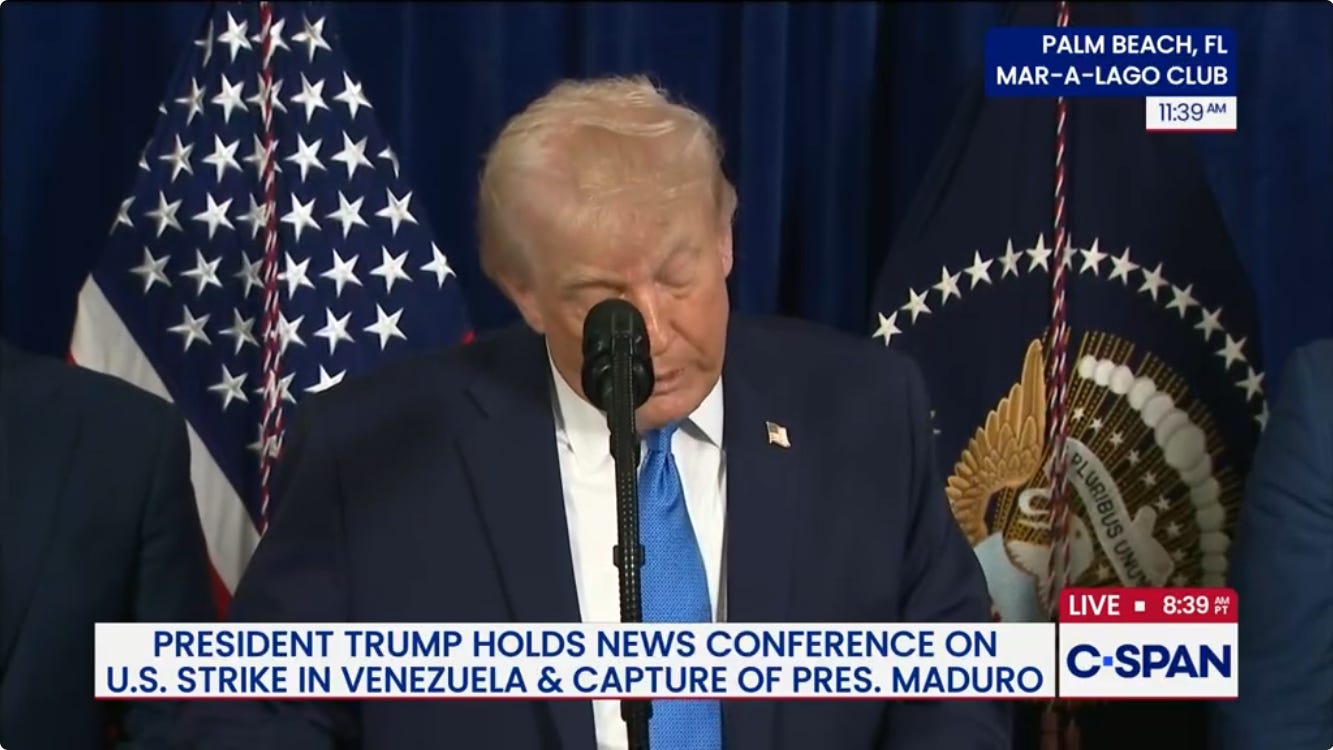

Or, as The New York Times put it this morning, “President Trump announced that U.S. forces had carried out ‘large scale strike against Venezuela’ and were taking President Nicolás Maduro and his wife to New York.”

The headlines are usually bad when I reconsider Huxley’s essay.

The last time was at the beginning of the yearslong siege of Gaza by Israeli forces, which has involved members of the Israeli military dropping bombs on hospitals and schools, using violence to disrupt the flow of food and medicine to starving people, and shooting aid workers. According to UNICEF, as of October, Israeli soldiers had killed or permanently injured over 64,000 children in Gaza.

In the United States and other countries, it became unofficial (and sometimes official) policy in many places to discourage and even punish criticism of Israeli government actions against people in Gaza, and relatively common practice to accuse anyone of making them of antisemitism (including Jewish critics of Israeli policies).

One reason I shared those pieces without comment at the time was that I wasn’t sure how the conflict in Gaza would develop; the other was that, to be honest, I was afraid of the repercussions of suggesting that it could be wrong for Israel to react to the terrorist violence carried out by Hamas with its own violence against people in Gaza who posed no direct threat to them. (To be clear, it’s obviously wrong to respond to violence by killing children and other innocent people. It’s wrong to starve people. It’s wrong to kill identified aid workers. It’s wrong to bomb hospitals and shoot aid workers. It’s wrong to tell civilians to leave one part of their country for another, and then to bomb them in the second place.)

Of course, the resistance to, or even suppression of, talking about the raw reality of violence tends to support Huxley’s point:

War is enormously discreditable to those who order it to be waged and even to those who merely tolerate its existence. Furthermore, to developed sensibilities the facts of war are revolting and horrifying. To falsify these facts, and by so doing to make war seem less evil than it really is, and our own responsibility in tolerating war less heavy, is doubly to our advantage.

President Trump, in proclaiming the actions he evidently ordered, called bombing Caracas and other Venezuelan cities, “a large scale strike” on Truth Social. He called the attack an “operation”.

Perhaps this goes to show just how ingrained this tendency to use euphemisms and code words to describe the violence of wars and warlike actions. Trump seems to be interested in projecting power and violence, and disinterested in even appearing to follow traditional norms or even US and international laws. His “secretary of war” Pete Hegseth, has loudly bemoaned the supposedly onerous restrictions on soldiers which are theoretically imposed by rules of engagement.

But even those rules of engagement, while important in a practical sense, also serve as what the philosopher Jean Baudrillard might have called a “simulacrum” of a moral war: just as Trump seems to have engaged in campaign of murdering people he alleges are drug traffickers on boats and at docks in order to create the appearance that we were at war with Venezuela before this weekend’s events, the very idea that some killings are not murder because they are conducted according to the “rules of engagement” can serve to support the premise that war can ever be just or moral. If there is a “wrong” way to kill people, that creates the sense that there is necessarily a “right” way.

Classical logic would require us to reject “just war” as an unquestioned premise, and instead ask ourselves and each other if we can look at the world as it is and create a rational and consistent argument that sometimes dropping bombs on people— including people who have not attacked us, including people who are clinging to wreckage in the middle of the ocean, including people who maybe just happen to be at or near a dock in Venezuela— is justified. Or, failing that, maybe we could ask whether war, while always unjust, is sometimes a “necessary evil”.

But Huxley’s point seems to have been that many of us do not want to pursue those questions. As he writes, “the mere word ‘enemy’ is enough to keep us reminded of our hatred, to convince us that we do well to be angry.” And by focusing on Maduro, a figure who faces a great deal of resistance at home and abroad because of his policies (including extrajudicial killings and, perhaps ironically for President Trump, “arbitrary detentions”)— in other words, an “enemy” of many people— Trump and many media outlets— intentionally or not— obscure the unknown number of civilians who were likely killed in the most recent attacks, and the people definitely killed in the previous boat strikes.

Whatever the actual motivations for these attacks, it’s virtually impossible they have anything to do with fighting the war on drugs (because Trump just pardoned former Honduran president Juan Orlando Hernández for drug crimes) or with promoting democracy in South America (because Trump openly idolizes former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, and arguably used him as inspiration for his extrajudicial killings of “drug dealers,” and, more obviously, because he just said he planned to “run” Venezuela, himself, in the immediate future).

It’s much more plausible that Trump and his advisors believe that he and/ or the United States will benefit politically and/ or monetarily from toppling Venezuela’s current government and perhaps helping to install new leadership which is willing, for example, to sell the United States crude oil at better rates (or, as Trump suggested today, to just take over the country himself). (These are extremely unoriginal ideas with a long and destructive history in Latin America; see, for example, the origins of the term “banana republic”.)

It’s profitable for Trump, and for many Americans, not only to avoid asking too many questions about the legality or practicality of bombing human beings in Venezuela and in international waters, but to avoid thinking too hard about the morality and human costs of state violence in general.

At least 115 people lost their lives in the lead-up to this weekend’s bombing, and it’s hard to believe that the United States and perhaps other countries aren’t on a path to bomb, shoot, and otherwise kill and harm more human beings in the near future. All I can offer is that it may be a good time to heed Huxley’s warning about the manipulation of language. Whether or not a person ultimately supports the actions taken by their country, it might be good to acknowledge that those actions, in this case, involve Americans, working for the American military and intelligence agencies, blowing other human beings to pieces.

As George Orwell wrote in his 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language,”

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties.

Amen!