There Will Be Blood

An all-too-relevant parable about the horrific nature of greed (and oil lust).

Well, I'm a vampire, baby,

Sucking blood from the earth

Well, I'm a vampire, baby,

I'll sell you twenty barrels worth

—Neil Young, “Vampire Blues”

Their frail human nature was subjected to a strain greater than it was made for; the fires of great had been lighted in their hearts, and fanned to a white heat that melted every principle and every law.

—Upton Sinclair, Oil!

We need total access. We need access to the oil and to other things in their country that allow us to rebuild their country.

—President Donald Trump, answering questions about the Jan 3 bombing of Venezuela (Jan 4)

I had been meaning to re-watch Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007) anyway.

It took me two sittings to finish the film this time around, and the second of these proved to be an unintentionally meaningful time to watch it, because on the previous day, United States intelligence and military personnel had bombed Venezuela, killing an estimated 80 people, and had captured the president of the country, along with his wife, in what appears to be an illegal use of force without Congressional approval.

By the time I had finished watching the film, President Trump had made explicit his (unsettlingly vague) plans to seize the moment to gain control over the country’s oil reserves, possibly the largest in the world. The heavy focus on stealing/ overseeing Venezuela’s oil ties Maduro’s capture to the larger history of American adventurism in Latin America, and the even larger history of deadly, catastrophic conflicts throughout history that were designed to steal/ control oil.

That Maduro is guilty of terrible crimes against his people has not been a significant part of the Trump administration’s justification for his probably illegal capture: as historian Timothy Snyder, author of On Tyranny, recently pointed out,

The abduction of Maduro was not about naming his crimes, but about ignoring them. The worst thing that Maduro did is just what Trump is beginning to do: killing civilians and blaming them for their own deaths.

There Will Be Blood is a horror film about greed and oil.

In an essay last July for Screen Rant, Shawn Lealos argues that There Will Be Blood is a vampire film, and I think that’s a compelling argument. Others, including Neil Young in his bleakly funny 1974 track “Vampire Blues” have made the connection between vampire fangs and oil derricks, between draining a body of precious blood and draining the Earth of valuable oil.

In the final sequence of the film, main character Daniel Plainview, a ruthless self-made oil man, tells his foil Eli Sunday, an evangelical preacher who has at this point ruined himself speculating in the oil market, “Every day I drink the blood of Lamb from Bandy’s tract,” a metaphor that not only connects oil and blood, but which suggests a profane repurposing of the blood of Christ.

During the same scene, Eli tells Daniel, “I’ve let the devil grab hold of me in ways I never imagined.”

I would go a step beyond the vampire interpretation, and argue that There Will Be Blood is a horror movie about demonic possession.

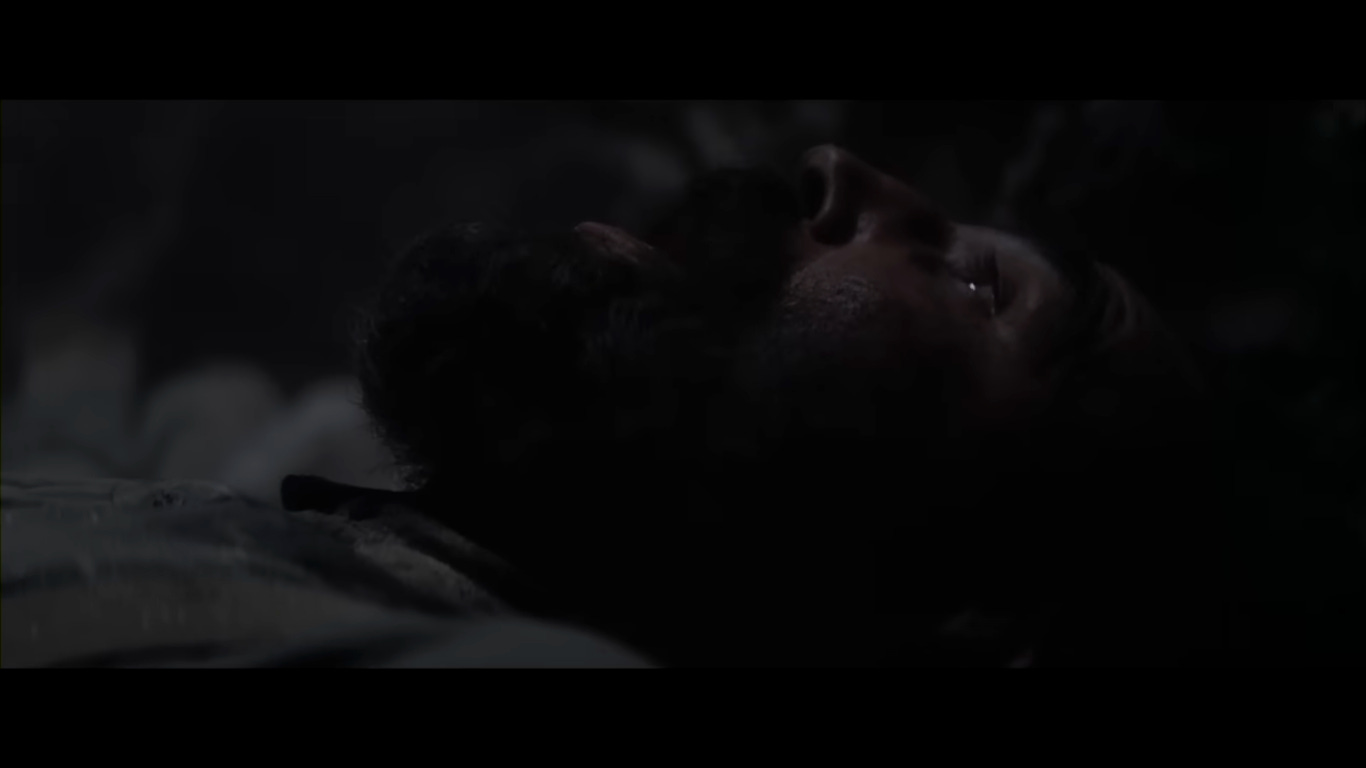

In the film’s nearly wordless opening sequence, Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis) descends into a dark hole on a sandy plain, plants dynamite and climbs out. After an explosion, he begins to climb back down, only for a rung of his makeshift ladder to break and send him tumbling down.

The screen cuts to black for a significant amount of time.

The way he gasps for air as he lays at the bottom of the well, leg broken against the wall, suggests a violent return to life after having the wind knocked out of him. And it suggests that something else could have seized the opportunity to get in, as well.

Plainview literally drags himself back to civilization to have the silver he has discovered assayed, and then the film flashes forward several years. To my eyes, Day-Lewis plays Plainview as almost a different person, still stooped and scarecrow-like, but now with a limp, and perhaps a madder gleam in his eye, his shaggy prospector beard replaced with the stylish moustache he will wear for the rest of the film.

In the interest of being able to continue this newsletter, I’m temporarily paywalling this piece. But I will share it again without a paywall in a few days. If you can afford a paid subscription, I really appreciate it!

That this opening sequence is an invention of the film— Upton Sinclair’s novel Oil!, told largely from the point of view of “Bunny,” the son of oilman J. Arnold Ross, begins after Ross has already had considerable success in the oil business. We only see Ross/ “Dad” as a suit-wearing, wealthy, and powerful former roughneck. His dialect, which, interestingly, Day-Lewis swaps for a strange, stilted, mid-Atlantic style in the film, is the only hint that the oilman wasn’t always a member of the upper class.

The sequence doesn’t give us much more insight into Plainview’s past or character, but it does start the film with his near-death plunge into the well.

And the film goes out of its way to present oil wells as tunnels into a profane, even supernatural place. Oil in the film is invariable sludgy and black. At least three times, ropes meant to haul tools up and down the shaft fail. On at least one of these occasions, the knot in the rope which will be used to lower tools is clearly tied with the same knot as a noose. When a falling piece of machinery kills a worker who is toiling in the whole next to Plainview, the surviving Plainview cowers away from it and when he uncovers his face has been made almost completely black by oil.

In a previous scene, the dead man has been shown anointing his baby’s head with black oil, which in the context of the film, particularly in the context of Jonny Greenwood’s alien-sounding score— which often recalls the dissonant drones of György Ligeti’s music as used in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Plainview’s “son” HW— a name that seems to deliberately call to mind former President George Herbert Walker Bush, and perhaps his dynastic passing of the torch to his son, George Walker Bush— is that baby. (Of course, many have argued that America’s long and bloody war in Iraq, begun in 2003 during the second Bush administration, was at least partly, and perhaps primarily, about gaining access to Iraq’s oil reserves. In any case this context is inextricable from the film, which was released four years into “Operation Iraqi Freedom”.)

There Will Be Blood’s main character subverts a tradition of tying the quest for oil to a quest for spiritual salvation.

In his book Anointed by Oil, historian Darren Dochuck argues that tying the search for oil to a spiritual calling was the norm, rather than the exception, in America during the period depicted by the film. Oil speculation could be a form of prophecy. An oil find could represent the blessing of Providence. The all-encompassing quest for oil could be America’s “manifest destiny”.

(There are major spoilers for There Will Be Blood ahead.)

It wouldn’t be unreasonable for a character like Eli to “bless the well,” as he asks Daniel to allow him to do. Setting up an intensifying conflict throughout the film, Plainview snubs Eli at the last moment. Shortly thereafter, a man dies in the well, and then an explosion catches the derrick on fire and renders HW deaf. Eli implies it is because Daniel would not allow him to bless the well that these events happen.

In this sense, Daniel and Eli seem like two pieces of the same broke vessel, the pious oilman type unnaturally divided into a preacher/ prophet (Eli) who compromises himself to build his church by dealing with a voracious, apparently nihilistic oilman driven, according to Plainview himself, by purely by anger he has “built up” over the course of his life, and by “a competition in me”. (Plainview tells a man he believes to be his long-lost brother, “There are times when I look at people and I see nothing worth liking. I want to earn enough money I can get away from everyone.”)

Ultimately, Eli and Daniel cannot coexist in the film; after duping Eli into proclaiming that he is a “false prophet” and that “God is a superstition,” he smashes Eli’s head in with a bowling pin in the most literal resolution of the film’s title.

On a plot level, this ending may make little sense. As a way of making the themes of the film concrete, it seems to be the only ending that could make sense. Roger Ebert once wrote that, in comparison with the title character of Citizen Kane, Daniel Plainview “regrets nothing, misses nothing, pities nothing”. As a metaphor for oil madness, this seems to be a feature, not a bug.

There Will Be Blood’s relationship to American history

There Will Be Blood is to the history of the oil boom what Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian is to Western outlaws. Like McCarthy (whose revisionist Western No Country For Old Men the Coen Brothers, incidentally, adapted the same year) Anderson cuts away pretty much any element of history or reality that interferes with the abstracted themes and imagery he is playing with.

Whereas in the novel Oil! Bunny’s father is a driven businessman who nonetheless exists in a world of norms and laws— he rents a furnished home for his family, he endures visits from state inspectors, he oversees the use of then-modern industrial technology to drill thousands of feet into the California soil, and he has to navigate the politics of employing and getting along with other people— Plainview exists in an alternate reality where he is often digging into the ground by hand, in a seemingly primordial, primitive wasteland of sand and shacks. While J. Arnold Ross is apparently divorced or estranged from Bunny’s mother, Daniel Plainview seems entirely uninterested in marriage or romance, steadfastly refuses to talk about his past, and “adopts” (or steals) H.W. after the boy’s father is killed in Plainview’s well.

While Oil! was inspired by the real-life Teapot Dome scandal— which, like the current crisis in Venezuela, involved a US President apparently using national oil policy to enrich his associates— the film never depicts law, government, or much in the way of what would have passed for “civilization” in the American southwest of the early twentieth century.

In the novel, police speed traps, local ordinances, and state laws are presented as constant obstacles from the point of view of Bunny and Dad. The West of the novel isn’t very wild; the West of the film is barely, and only uneasily, populated by humans. During this rewatch, it often reminded me of Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015), a film that takes place on an isolated 1600s New England ranch.

In this way, the film seems to represent ideas about history that are bigger and more abstract than the events of the novel.

For example, the outbreak of World War I is central to the plot of Oil!

“Dad” is willing to profit from the new oil demands in Europe brought about by the chaos and destruction of war.

And a major impetus for American involvement in the conflict was— you guessed it— the search for oil.

According to Scott Anderson’s Lawrence in Arabia, by 1915 Standard Oil Company of New York was already using conditions in the Middle East caused by World War I to its advantage:

What the bosses are 26 Broadway had come to realize was that so long as the Europe-wide war continued— and, just as crucially, so long as the United States kept out of it— they had the vast territories of the Ottoman Empire practically to themselves… The scheme traded on Turkey’s desperate need for oil, a vital commodity if it was to have any hope of competing militarily. The oil coming through Socony’s [Standard Oil Company of New York] Bulgarian smuggling operation is was a pittance compared with what was needed, and to meet this need Standard held out a possible solution: Palestine.

In order to achieve their goal, Standard Oil bribed the secretary of the Turkish Senate, placed their man in the region on a legislative drafting committee, and helped rewrite Turkey’s mining laws. (This seems like a plausible indicator of what Trump officials may mean when they repeatedly indicate that they would like to select leaders in Venezuela who are “cooperative” with American interests.)

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that a scene in which Daniel Plainview meets with Standard Oil feels, uniquely, like perhaps he, for once, is the one on the human side of a Faustian bargain. (That it falls apart because a Standard representative both suggests he isn’t taking care of his “son,” and that he can’t handle his oil discovery without the giant company, is also a telling moment for a character who is often inscrutable by design.)

The film seems interested in the broad strokes of what the novel is saying about American capitalism.

Anderson has, rightly, downplayed the film as an adaptation of the novel. He reportedly only used about the first 150 (of over 500) pages of the book, and changed the title, the names of major characters, and most of their backstories and characterizations.

But the connections are still there.

An early speech by Plainview (post-transformation), in which he tells his audience, “If I say I am an oilman, you will agree” is nearly identical to a speech given by Ross in the novel, other than the change from Ross’ southwestern dialect to Plainview’s clipped and intense speech patterns. This is followed by a similar disagreement with the townspeople— who in the film seem like they are fighting for the very soul of the town— which ends with both Ross and Plainview saying “I wouldn’t take the lease if they offered it as a gift.”

Paul Watkins, a character idolized by Bunny who inspires him to engage more and more with labor rights and socialist causes, is more or less Paul Sunday, one of two characters played by Paul Dano in the film. That said, Paul apparently only appears in one scene in the movie (this is made ambiguous by the fact that Dano plays both Paul and Eli in the film, and the two never appear together), while Paul reappears throughout Oil!

Abel Watkins is more or less Abel Sunday, a hard, religiously intense father.

And the plot of the first part of the novel roughly sketches out the majority of the film’s plot: “Dad” and “Bunny” come to town in search of oil, the bickering townsfolk can’t agree on oil lease, so the oilman character finds wilder places further from the discovery well to dig at lower rates.

In this part of the novel, though, “Dad” is more prosaically corrupt: he bribes officials, he tries to get away with speeding. But he is also depicted as likeable to his men and caring to his family. He is a portly, gregarious roughneck, unlike the haunted scarecrow played by Daniel Day-Lewis.

Plainview seems almost beyond corruption. Although he ostensibly wants money, we rarely see him spend much of it on anything other than building more oil derricks, more oil pipelines, more oil wells. Instead, he seems to be a kind of corruption, in the spiritual sense, leading others to give up their principles in order to further his quest for oil.

Both the film and novel depict greed as a kind of satanic force.

Early in the novel, Sinclair rights, of an otherwise kindly character seduced by the prospect of striking it rich with an oil lease, “Yes— Satan had brought her there, and set her on a rabbit-hutch, and was showing her all the kingdoms of the earth!”

This kind of language recurs throughout the book, tying greed not just to human foibles, but to an evil that does real violence to people.

But while Sinclair’s tone throughout the book is very similar to that of a satirical humorist like Mark Twain (the book bears particular similarities to Twain’s The Innocent’s Abroad), the film takes similar ideas and ratchets them up to a horror movie intensity.

Plainview is often depicted in firelight, or other sources of red light. The black ooze of oil is constantly filmed as a kind of corrupting, primordial force.

In the final scene, Plainview drops any appearance of sanity or goodness, chasing Eli around his private bowling alley— part of an opulent mansion where he seems to live in drunken squalor and misery— and screaming, “I am the third revelation. I told you I would eat you up!”

While the film is deeply complex and often impossibly ambiguous from the point of view of a straightforward reading, the connection between the lust for oil and the corruption of the soul is clear. And since neither text operates on an especially religious register— for example, neither is especially interested in whether Eli can actually heal people with his faith, or whose religious beliefs are correct— the allegorical messages seems to be that the kind of greed that compels Plainview is a greed that comes from a yawning emptiness within, whether within an individual or in a culture.

It seems clear what both book and film would tell us today, as the US enters a new period in which its leaders openly declare their intention to dominate a sovereign nation’s oil reserves.

Will we learn from the long history of such adventurism, and from the intense destruction and anti-democratic regime changes in the Middle East, Latin America, and other places around the world?

I hope so.