Suspiria (2018) and the Horror of Denying History

Germany's reckoning (or not) with the Holocaust, the Suspiria remake, and what we should learn.

Warning: Mild spoilers for the film Suspiria (2018).

People can organize themselves to commit crimes and call it magic.

-Josef Klemperer, Suspiria (2018)

As part of our annual Halloween-season movie tradition, my wife and I recently watched the 1977 giallo classic Suspiria and its 2018 remake. Our conversations as we watched led me to an excellent Vulture article from a few years ago called “A German History Primer for the Confused Suspiria Viewer,” by Nate Jones.

That 2018 remake divided critics at the time and flopped financially (with the caveat that Amazon Studios evidently didn’t give it a wide release commensurate with its relatively large budget) but it might be due for a reappraisal in light of what happened in the intervening six years.

The 1977 Suspiria centers on an American dancer who enters a mysterious German dance academy. It involves witches, the gory murders of young female protagonists (with a leering camera that seems a little too excited about some of the violence), intense, nearly psychedelic colors and set designs, incredible synth music, and not much in the way of a coherent plot.

The 2018 Suspiria, directed by Call Me By Your Name director Luca Guadagnino, takes up the same basic premise, but adds a more complex plot involving two kinds of mounting dread: an A-plot based on the original film, concerning a young dancer who enters a Berlin ballet academy as the leadership is engaged in a supernatural struggle for power, and frequent intrusions from a B-plot that involves the connection of at least one of the students to the Red Army Faction (RAF)— or “Baader-Meinhof Group” — a real-life Communist militant group carrying out murders, bombings, and hijackings, in reaction to the post-WWII German government— a period sometimes called the “German Autumn”.

The year before the events of the film, the RAF collaborated with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine to hijack a French airliner, taking 103 hostages. An Israeli commando team killed all of the hijackers and rescued the hostages. Also in 1976, one of the group’s main leaders, Ulrike Meinhoff, had hanged herself while in prison for the earlier murders.

Part of this larger political context of 1977 Germany is an intensifying conflict over the delayed reckoning with the reality of the Holocaust. The RAF, specifically, sought to connect contemporary German authorities with the fascist Nazi regime, and with Western imperialism. Symbolically, the fact that— spoiler alert— Tilda Swinton plays the leaders of both of the ballet school factions— Madame Blanc and Mother Markos— as well as the primary witness character/ viewer stand in, seems very significant. (The fact that Swinton often resembles a young David Bowie, who in 1976 was in his “Berlin period,” might also not be an accident. Bowie was definitely in Berlin when the events of the movie take place, and one shot features a prominent Bowie poster in a character’s room.)

According to historian Thomas Speccher, 1968 (a year which, not incidentally, seems to hold a kind of talismanic significance for conspiracy theorist/ voucher promoter Chris Rufo, author of the American anti- “CRT” panic, because it is often seen the height of intellectual Leftism in America) had marked the beginning of a shift in the way the country characterized the Holocaust in the post-war period (although Speccher says those who pushed for a more truthful reckoning with those events were still a minority).

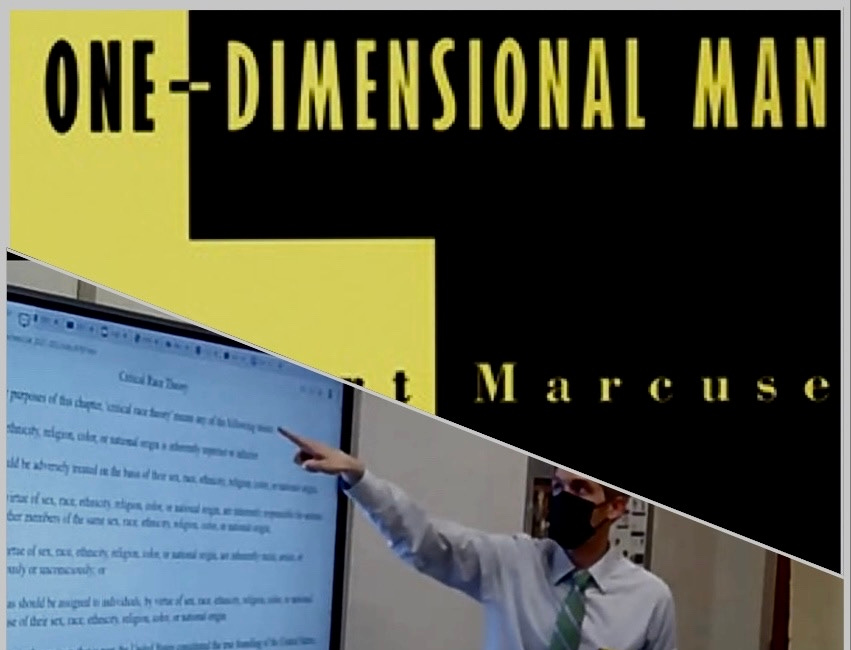

Banned Thoughts: Critical Theory

Just as people know or feel that advertisements and political platforms must not be necessarily true or right, and yet hear and read them and even let themselves be guided by them, so they accept the traditional values and make them part of their mental equipment.

This period is seen as a reaction to the way large numbers of Germans embraced a revisionist vision of the Holocaust after World War II, avoiding discussion of the concentration camps, and continuing to embrace Nazi ideology.

In the Vulture piece, Jones writes,

As [scholar and Postwar author Tony Judt] details, in 1946, 37 percent of Germans polled in the American Zone said the mass murders of the Holocaust were “necessary for the security of Germans.” Even in the early 1950s, that same percentage of West Germans said the country would be “better” if it had no Jews, while 25 percent had a “good opinion” of Hitler. As the years went on, these sentiments subsided, but the sense of victimization did not. Hitler remained a convenient scapegoat, as conventional wisdom held that the crimes of the Nazi era were his and his alone.

Psychiatrist Dr. Josef Klemperer (spoiler: he’s a third character played by Swinton, this time in old-age drag), opens the film treating Patricia (Chloë Grace Moretz), a dancer with RAF connections who disappears early in the film, Klemperer is clearly mourning his wife. (Another spoiler: Around the midpoint, we learn that she has been missing since 1943, likely taken by the Nazis.)

While no one explicitly talks much about the war or the Holocaust in the film, Klemperer is a living reminder of the reality of the war. Not coincidentally, he is more clear-eyed about what is happening in the ballet school than nearly anyone else in the film, even if he is slower than the audience to understand the supernatural elements at work.

Later, in an obvious mirror of what happened to his wife, he watches a young woman he has been trying to help as she is dragged away, unable or unwilling to do anything to save her.

Still later, in a conversation in which he explicitly draws a parallel between Patricia’s connection with RAF and her “delusions” about the witches, Klemperer says “love and manipulation, they share houses very often”. And protagonist Susie (Dakota Johnson) asks at one point, “It’s all a mess, the one out there, the one in here… Why is everyone willing to think the worst is over?” In other words, the film certainly wants us to connect the confusion and intrigue in the ballet school with the historical context of a complex struggle between the avant-garde (ballet, Bowie, experimental art), the radical (the RAF, the struggle over leadership in the school), and the reactionary (the contemporary government— at least as envisioned by the RAF— and Holocaust deniers).

As the Allies planned the rebuilding of the German state, they initially planned to hold Nazi leadership responsible for their crimes, but according to some historians they quickly determined that doing so would clash with their other goals.

As Jones writes,

Though the Allied powers did hold Nazi leadership accountable for crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials, as Tony Judt writes in Postwar, eradicating lower-level Nazis from public life soon proved “not practicable.” Germany after the war contained 8 million former Nazis, many in professions the Allies relied upon to rebuild a functioning society, like doctors, judges, and civil servants. And, Nazi or not, ordinary Germans often resisted reckoning with the violence carried out in their name. The Allies made watching footage of concentration-camp scenes mandatory for those who wanted ration cards; Judt quotes the author Stephan Hermlin, who reported that most of the audience in one Frankfurt theater simply turned their heads away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Other Duties (as assigned) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.