Other Duties as Assigned, Part I

South Carolina’s one-sided teacher “contract” and the punitive nature of the state’s school district retention strategies.

This piece is part of an ongoing series. Here is Part II.

“Performs other duties as assigned by the Building Administrator(s)”

-Various South Carolina School Districts, “Certified Teacher Job Description”

"‘Everyone strives to reach the Law,’ answers the man, ‘so how does it happen that for all these many years no one but myself has ever begged for admittance?’ The doorkeeper recognizes that the man has reached his end, and, to let his failing senses catch the words roars in his ear: ‘No one else but you could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you. I am now going to shut it.’”

-Franz Kafka, “Before the Law”

A circuit court judge in Wisconsin recently lifted an order sought by hospital group ThedaCare which had legally blocked seven employees from leaving to take new jobs at another hospital. Joe Veenstra, a labor lawyer interviewed by the New York Times about the case said, “We’ve definitely entered an alternate universe… Now we have managements incapable of controlling labor and asking courts to prevent the free market from happening. It’s just, we’re living in an upside down world right now.”

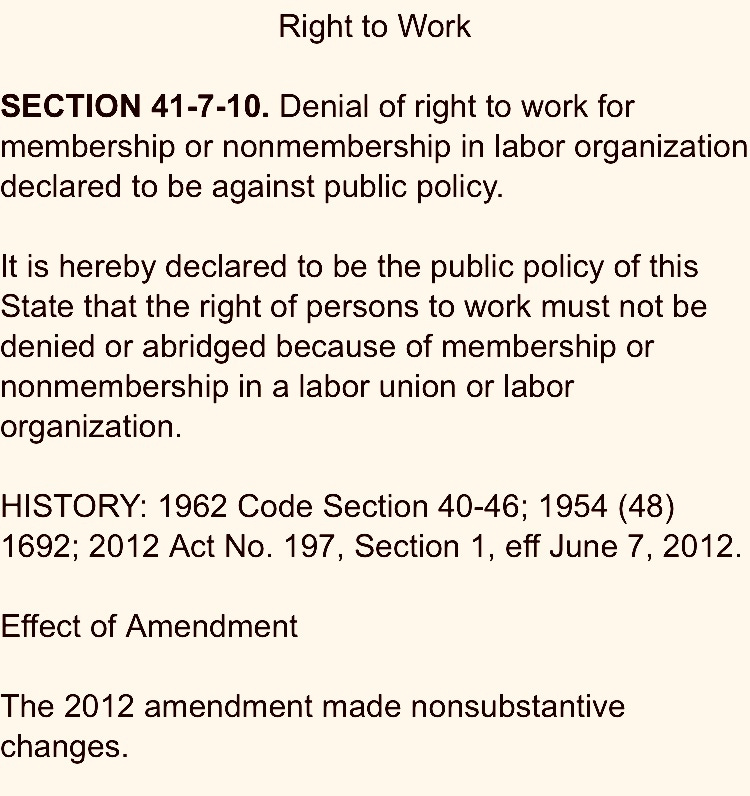

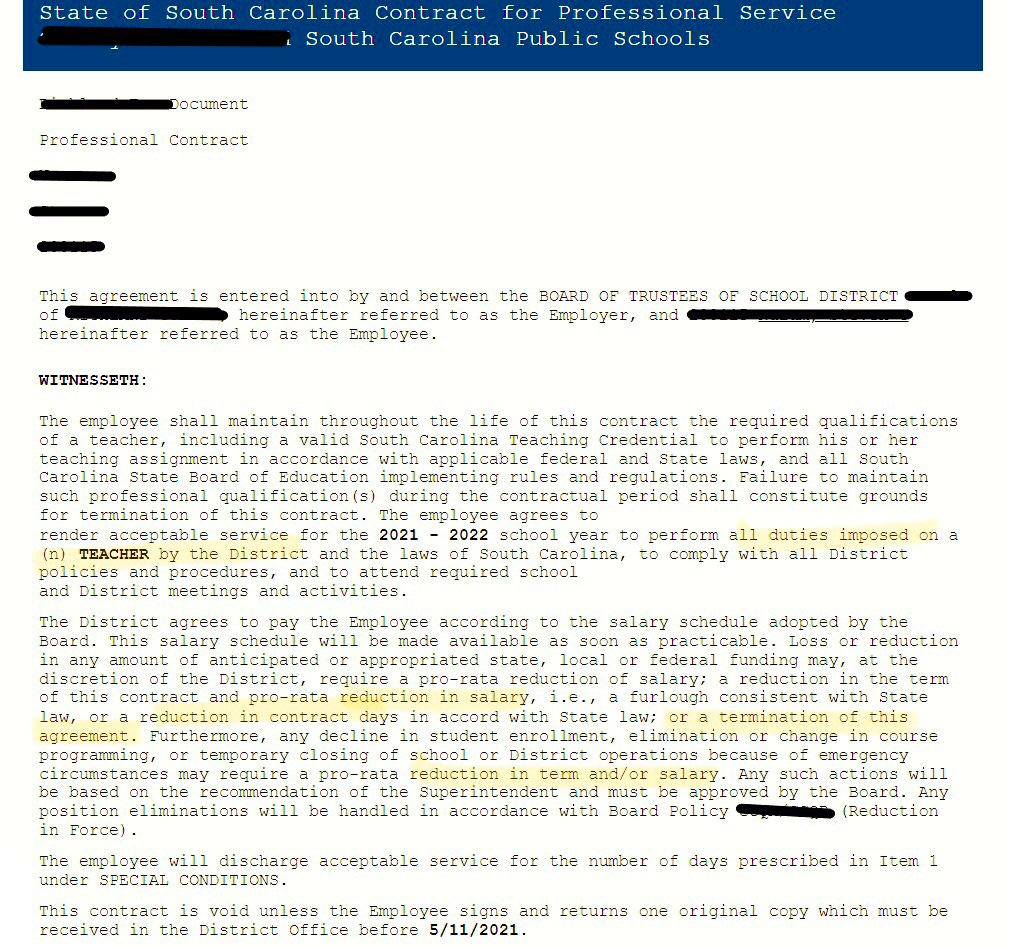

We could call that upside down world “South Carolina,” where state law and State Board of Education regulations have long allowed school districts to hold teachers to one-sided employment contracts that lock them into 190-day terms of service, without the districts being required to disclose or adhere to agreements about specifically what teachers will teach, how much they will be paid, and which specific extra duties they will be assigned. The main enforcement mechanism for these contracts is that districts have the power to direct the South Carolina Board of Education to revoke a teacher’s professional license, the document required to hold most public school teaching jobs. This is quite a look for a state which traditionally prides itself on a zeal for the “free market” and “the right to work,” and school boards have certainly been willing to not only exploit the law but also to use it as a scapegoat in their own internal decisions.

Traditionally, South Carolina teacher contracts and job descriptions, like one-sided employer-employee agreements in other professions, have contained a catch-all phrase generally worded as “other duties as assigned”. The phrase is notorious to the point of being almost an in-joke or bogeyman among school staff: any time the boss wants you to do something that isn’t your job, it’s “other duties as assigned”.

I’m not sure if the phrase has taken on the same symbolic importance and Kafkaesque humor for non-teachers that it holds in education circles, but I wouldn’t be surprised. It is, after all, the unscrupulous manager’s dream to be able to solely dictate what an employee does at work without the inconvenience of negotiation. It is the kind of detail you know has to be in the job agreement between Gregor, the salesman-turned “monstrous vermin” of “The Metamorphosis,” whose boss sends a lackey to his house to catch him malingering on the first day he has missed work in five years (on account of his literal transformation into a nonhuman creature).

That, of course, is the essence of “Right to Work”: it is the right to live free of labor protections, to enjoy the freedom of a worker who does not own their labor and cannot negotiate the cost of having their labor taken away at the discretion of an employer. It is not a unique freedom for schoolteachers, but it is a driver of the teacher retention and recruitment crisis, and it has taken on an even more sinister dimension during the pandemic, when teachers I know have left the profession, reluctantly, for health reasons, only to have their district challenge their certificates. Highly qualified people who would have returned to the profession when it was safe now do not have that option, and it’s hard to see how anyone benefits from that.

People from less labor-hostile states often express surprise or even disgust that employees in South Carolina and other “Right to Work” states would enter into agreements with a district in which every benefit weighs toward the district, in which literally no formal protections are offered to the employee, and in which all terms can be changed at any time by the employer. (Incidentally, thanks to SC’s 2000 Branch v Myrtle Beach state Supreme Court ruling, even the small worker protections included in the the anti-labor “Right to Work” state law— namely, the right to join a union, which is what the firefighters in the case were seeking— don’t apply to teachers and other public employees.)

While the intent of the “other duties” language is likely to protect districts from lawsuits by vaguely encapsulating anything other than teaching the school leadership might require, the idea of a freewheeling license to assign extra duties to school staff has not been without legal challenges. In 2019, a Cherokee County, SC, teacher filed a class action lawsuit against her district for requiring her to work additional hours without compensation, and to pay for school supplies out of her own pocket. For the Cherokee County teacher, the “other duties as assigned” included running a concession stand outside of school hours, for free, and paying for school supplies out of the teacher’s pocket (a common expectation and practice for teachers which I don’t think is often formally demanded by the district, as it apparently was in this teacher’s case).

Sherry East, of the South Carolina Education Association, called the requirements at issue in the Cherokee case “involuntary servitude,” and I think her assessment was fair. How else to describe, at least, the most extreme cases, such as a teacher who is tasked with job functions no reasonable person would associate with teaching, without additional compensation, or a teacher with legitimate reasons to leave one job who has their main means of income, their teaching certificate, stripped away for trying to find better working conditions?

The teacher’s full complaint can be read here.

During a recent discussion on the Pressure Points podcast, Richland One school board member and current president of the South Carolina School Boards Association Jamie Devine quoted from South Carolina Board of Education regulation 43-206:

“Any teacher who fails to comply with the provisions of his contract without the written consent of the school board shall be deemed guilty of unprofessional conduct. A breach of contract resulting from the execution of an employment contract with another board within the State without the consent of the board first employing the teacher makes void any subsequent contract with any other school district in South Carolina for the same employment period.”

Devine continued, “So that kinda sends the cause for the resignation and why we do sometimes, school boards do what they do.”

He went on to suggest (incorrectly, and for reasons that Richland One School Board member Robert Lomanick explains in very helpful detail in a video post on the issue of teacher contracts) that school boards’ hands are essentially tied in forcing employees to remain in their contracts even when they find other employment opportunities or ask to be released for other legitimate reasons.

But districts’ hands are not tied, as even Devine seems to acknowledge in the same podcast when he references a time when people were “lined up” to accept teaching jobs and, he says, boards were more inclined to release a staff member who “put in her two weeks’ notice”. State Board policy allows school districts to challenge a teacher’s certificate after the board has chosen not to release the teacher, and yet the teacher has decided to seek employment elsewhere, but the board is in now way required to do so. As Lomanick points out in the video, school boards still release teachers from contracts all the time, notably to allow them to move to

jobs in the district office or at the State Department of Education, without losing their teaching licenses. As Devine seems to suggest, the motivation for playing hardball with teachers seems to be, not a requirement of the law or even a belief on the part of school boards that to seek a change in employment is somehow wrong, but simply the failure of school districts to attract replacement candidates and the desire of the district to compel an employee who no longer wants the job to stay in the job, anyway.

Imagine for a moment what it’s like to be a student in some classrooms where the teacher has asked to quit and has been denied. In my experience, most teachers in this situation still try to do the best jobs they can, but we’re human, and I have to believe that being trapped in a job while living in a state that might as well have “at will employee,” in Latin, as its official motto, has to make finding joy and enthusiasm in the work very difficult.

And, of course, as I’ll discuss below, the same logic behind retaining teachers through the threat of punishment is playing out in school districts’ approaches to responding to staffing shortages exacerbated by the pandemic.

Even if Devine were right (and he is not) in suggesting that holding teachers to burdensome and one-sided contracts is a requirement of the state, this hopefully sheds some light on why many people are reluctant (or unable, if their teaching certificates have been revoked by districts) to go into teaching jobs in South Carolina. In essence, the state and districts are arguing that by signing a contract that promises literally nothing to teachers and other certified staff besides a salary that may be reduced at the sole discretion of the district, the district and/ or the state of South Carolina own their teaching labor for 190 consecutive work days at a time, even if the requirements of and compensation for that labor change significantly. And ironically, while Devine and others suggest that the goal of such extreme measures is to keep teachers in the profession, revoking teacher licenses obviously reduces the already thin supply of available teachers each year, as well as making the profession less appealing to prospective teachers, who are in perhaps the best position to move to another state to start a career with some kind of guarantee of what the salary and work expectations will be.

This has always been a serious issue. During the pandemic, it has become part of a metastasizing school staffing crisis, and has allowed school distsricts to make demands on their labor forces that would be illegal in many fields.

The Fair Labor Standards Act “exempts” teachers from overtime, which is a nice way of saying that it allows employers to require them to work overtime without extra pay “if their primary duty is teaching, tutoring, instructing or lecturing in the activity

of imparting knowledge, and if they are employed and engaged in this activity as a teacher in an educational establishment”. The pandemic has exacerbated existing staffing conditions in schools to the point that many districts, unable to fulfill their obligation to staff schools in traditional ways, or to find and retain enough substitute teachers or other staff to cover vacancies, have begun to require teachers to regularly cover absent colleagues’ classes or classes with unfilled teacher vacancies, in addition to their regular duties. A November SC for Ed survey of about 1,600 SC school staff members found:

The majority of school staff surveyed (56%) reported being required to cover classes for absent staff members at least once per week, and responses to the open-ended question suggested that this was both significantly more often than in previous years (21% reported covering an average of 3 or more days per week), and more likely to add to staff burnout. 39% of those required to cover classes were not paid for doing so.

It is likely that as more teaching and other school staff positions have been vacated since November, these statistics have worsened.

In one South Carolina school for which I was able to access coverage data, and which is not exceptional in the way it has handled staffing shortages, teachers and other staff have covered, without additional pay, a total of at least 900 class periods. Many other classes without subs at the school were simply sent to sit in the auditorium or another area of the school with general supervision of several combined classes by a non-teaching staff member. In other words, there were over 900 times in a single school, within the first 104 days of the academic year, when the school district was unable to find a substitute teacher (who would have been paid for covering the class) and instead required a full-time employee or a non-certified staff member to do that absent sun’s job for free.

Districts taking similar steps would likely argue that the staff members required to sub were fulfilling the supervisory or even instructional parts of their job description, but I can say from experience and many conversations with coworkers this year that covering a class is not teaching or supervising in the sense of teachers’ normal jobs. It often means being thrown unexpectedly into a classroom full of unfamiliar students, in a subject area you don’t teach, and without any plans or materials to work from. Students may be understandably agitated because their normal teacher is out. It’s like babysitting, with little notice, for 35 strange children. (In other words, subs have a very difficult job, and should be paid more, and teachers who are subbing should be paid for that additional work.)

Being pulled to cover also means the loss of planning time for the day, which can mean lost time to grade student work, answer emails, eat lunch, or go to the bathroom.

In a year in which burnout is at an all-time high, this is the last thing we should be doing to teachers and staff, but districts are doing it more than ever before, because they seem to believe, possibly incorrectly, that the combination of the “other duties as assigned” language and State Board of Education regulations give them carte blanche to work school staff as much as they choose while being able to hold not only the threat of loss of job, but essentially of temporary loss of career, over the employee’s head as a stick without a carrot.

It seems clear that this stretches “other duties as assigned” to an unreasonable and potentially unenforceable breaking point. I expect and hope to see lawsuits resolve this issue. According to the Post and Courier, “Reckenbeil [attorney for the complainant in the Cherokee County lawsuit] argues the [Fair Labor Standards Act] exemption applies only when teachers are actually teaching, meaning they should be paid overtime when working non-academic functions outside of normal school hours.”

But whether or not courts side with school staff, our staffing issues will only get worse if schools continue to rely on “other duties as assigned” to cover every gap in the education system. A district superintendent I know once voiced to a group of teachers the concern that if the SC legislature passed a law requiring an unencumbered planning period for all teachers (meaning the planning period couldn’t be filled with required duties or meetings), he wasn’t sure schools could maintain all of their current functions. I replied that in my view school districts relying on the extra, non-contracted work of teachers and other staff were already a house of cards; if enough staff refused to do extra work without pay, under the current management approach, the whole system would collapse.

That was before the pandemic.

What makes staffing particularly tricky at this moment is that on the one hand, requiring teachers to sub and cover classes without pay saves districts money, and on the other, requiring non-certified staff (who are not “exempt” from overtime pay) to sub and cover classes could potentially cost districts additional money. But this is hardly an excuse in a year when districts have received an average of over $10 million in additional ESSER II funds, which are explicitly intended to deal with short-term issues brought on by the pandemic. Category 15 under “allowable uses” of ESSER II funds is “Other activities that are necessary to maintain the operation of and continuity of services in local educational agencies [which include school districts] and continuing to employ existing staff of the local educational agency”.

The state could immediately force districts to come up with more sustainable approaches to staffing by passing legislation like S. 348, sponsored by Senator (and gubernatorial candidate) Mia McCleod, and the similar H. 3246, which simply prohibit districts from penalizing teachers who choose to leave to take a better job offer. Imagine the improvements to the work environment that districts might implement if they were forced to try to retain employees through job improvements and negotiation of duties rather than threats.

Until then, I’m afraid too many teachers will feel like one anonymous teacher, who wrote:

“Each week something new comes up that requires teachers’ time and energy. As soon as we understand what is expected and how to implement it, something changes and we have to relearn it all over. When teachers speak out or share our frustrations, our support for students is questioned.”

-Anonymous School Staff Member, SC for Ed Statewide “Extra Duties” Survey

And that kind of working environment can only bode poorly for our state’s nearly 800,000 public school students.

This is a complicated issue that I plan to look into in deeper detail in a later post, hopefully after speaking with experts who can add more to the legal perspective. If you want to make sure you see that post, please consider subscribing below. (It’s free.)

Update: Here is Part II.

To hear my music: Bandcamp and other streaming services. See similar content in much shorter chunks by following me on Twitter.