“It happened whether it offends you or not.”

Some thoughts about Octavia Butler's genius and the evils of censorship, in anticipation of MLK Day.

“That book wasn’t even written until a century after slavery was abolished”

“Then why the hell are they still complaining about it?”

—Octavia Butler, Kindred (1979)“I would like to honestly say to you that the white backlash is merely a new name for an old phenomenon […] What I'm trying to get across is that our nation has constantly taken a positive step forward on the question of racial justice and racial equality. But over and over again at the same time, it made certain backward steps. And this has been the persistence of the so called white backlash.”

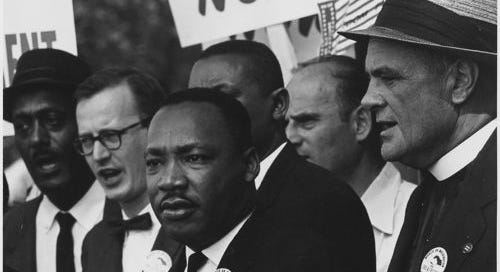

—Martin Luther King, Jr., “The Other America” (1967)

“…no monies shall be used by any school district or school to provide instruction in, to teach, instruct, or train any administrator, teacher, staff member, or employee to adopt or believe, or to approve for use, make use of, or carry out standards, curricula, lesson plans, textbooks, instructional materials, or instructional practices that serve to inculcate any of the following conc…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Other Duties (as assigned) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.