I am not a robot.

Teaching beyond "the bare facts"

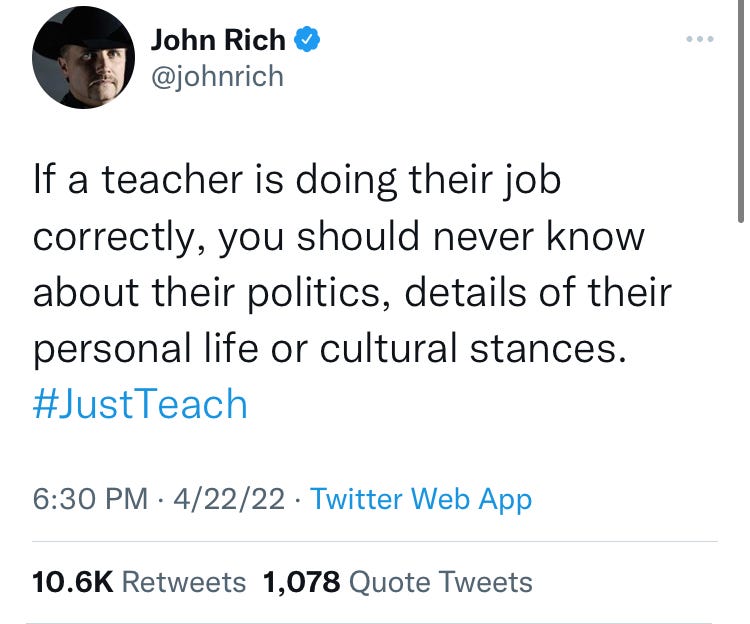

Updated April 24, 2022. To give some idea of how the public conversation around teaching has been going since I wrote the original essay in February, a tweet from the guy who sang “Save a Horse, Ride a Cowboy” dispensing pedagogical advice has over 10,000 retweets.

My memory of it is clearly-carved: a bright spherical hall, hundreds of round little-boy heads, and Pliapa, our mathematics teacher. We called him Pliapa— he was rather vintage and disheveled, and when the monitor inserted his plug from behind, the loudspeaker started up “Plya-plya-plya-tshhhhh,” and then the lesson began.

-WE, Yevgeny Zamyatin (1921), Translation by Natasha Randall (2006)

The word “robot” derives from a Czech word which means something like serf. It connotes forced, mindless labor.

Being, becoming, or being replaced by a robot were the central nightmares of a lot of early twentieth century science fiction. In the 1927 film Metropolis, a Frankenstein-like mad scientist type longs to build “The Man of the Future— The Machine Man!” against a backdrop of depressed, disposable underground workers and haughty, spoiled Roaring Twenties-style rich kids partying in paradise.

In post-revolutionary Russia, Soviet thinkers dreamed of the “New Soviet Man”: more efficient, more logical, more scientific. The new model for humanity in the industrialized and industrializing worlds was Henry Ford and his assembly line. The new prophet was a would-be visionary who is having something of a renaissance, Frederick Winslow Taylor, a rich-kid-turned-“scientific management” expert who popularized the invasive study and micromanagement of factory workers and other laborers. (Amazon even created high school curricular materials that included Taylor’s ideas. Maybe the next round of weird education bills will require us to use those.)

I am not a robot, despite the fondest wishes of many education “reformers,” “disruptors,” and “generalists”. My students, also, are not robots.

This week, the South Carolina House Education and Public Works Committee met to discuss five bills which critics have termed “anti-truth” bills. If you are from another state, chances are your state is passing some version of the same bills, possibly with exactly the same language.

During the committee meeting, which limited testimony to thirty citizens, Representative Melissa Oremus (R-Aiken) questioned/ lectured SC Superintendent of Education Molly Spearman on the bills, which, among other things, require curricula to be aligned with the highly-partisan 1776 Commission Report (parts of which are lifted from a Heritage Foundation article) and outlaw a series of “tenets” (or forbidden concepts, if you prefer) identified by the Heritage Foundation as representing “Critical Race Theory. (If it seems like the bills were largely written by the Heritage Foundation, many were, and whether or not the often hapless supporters on the committee know this is probably beside the point.)

Oremus, explaining the bills while ostensibly questioning Spearman on curricular materials and standards, opined, “I think the purpose of this, is to basically get back to us giving the standards that needs to be without the feeling and emotion into it, just presenting the bare bones and the facts”. I assume by this, she meant the series of bills; I’m not sure what she meant by “the bare bones,” but it doesn’t sound very engaging for learners. As for standards, I think Spearman, a former educator, has a solid grasp on the idea that academic standards are essentially the minimum skills and content a student is expected to master by the end of each grade year in each subject; Oremus seems to believe they are a much more specific and limiting set of of maximum content requirements.

The idea of teaching “without the feeling and emotion” is one that honestly perplexes me, and indicates a profound misunderstanding of what it is teachers do with students all day. Anyone who has taught or who knows teachers will probably laugh—or cry—at the thought that people running the state government may honestly believe an educator’s job can be boiled down to say facts towards children, or the thought that doing so is the only way to avoid forbidden concepts.

As a number of career educators and educational experts testified before the committee, engaging students emotionally and making connections to important personal and real-world learning are widely-recognized best practices in the field of K-12 education. When I invited Representative Oremus, on Twitter, to come to my classroom to demonstrate how to teach without feeling or emotion, she blocked me without responding (something that may be unconstitutional, and which has led to lawsuits against South Carolina House members in the past).

In one respect, I don’t blame her for not offering an answer: In the abstract, it is possible to imagine (maybe) a Platonic ideal of teaching in which pure information is somehow transferred from speaker to listener, without all of those troublesome distortions of perspective, bias, ambiguities of language, and, especially, those damned feelings and emotions. But I assume that for any intelligent person, this abstract ideal melts away pretty quickly at the prospect of trying to do it with real, living kids. And if it doesn’t— seriously— we have never needed subs more than we do this year, so please encourage anyone who doesn’t understand to sign up. (Really. I cannot stress how dire and dangerous the twin shortages in teaching staff and substitutes has become.)

Perhaps Representative Oremus realized she had been somewhat hasty (or was intentionally obfuscating) in suggesting that attempting to make education significantly more boring and meaningless was a good thing to require in state law.

A major thorn in the side of would-be reformers, disruptors, and destroyers of public education is that, as writer John Green says, “The truth resists simplicity.” Children are complex, adults are complex, history is complex, literature is complex, math is complex, and reality is complex. The relationships among all of these complex things are exponentially more complex. In her questioning of Molly Spearman, Oremus trotted out some familiar far-right talking points about BrainPop (it’s “leftist” because of “feelings,” and probably also because BrainPop materials have touched on the shouldn’t-be-but-is radical concept that Black Lives Matter) and Social Emotional Learning (SEL), and her suggestion seemed to be that children don’t need those pesky relationships with teachers if only teachers would lay “the bare bones and the facts” on them in presumably the blandest, least personal way possible.

And again I say, if that can be done (and I’m not sure anyone should actually want it to be done), please come and show us. I have been a teacher for fifteen years, and I have never known an effective teacher who didn’t care about the subject matter, didn’t try to engage the students in passionate discussions and debates, and didn’t have their own feelings and emotions about the subject. It is, of course, possible to express feelings and emotions without indoctrinating, brainwashing, or ideologically coercing students, and without sharing partisan views. I know this because I do it every single day of the work week, for hours and hours (and what sometimes seems like more hours) each day. I put out an invitation to all of the committee members who are on Twitter, as I did with Governor McMaster, Superintendent Spearman, and Senate Education Chair Greg Hembree (who was brave enough to take me up on it); so far no one has responded, although Representative Raye Felder did like the post in which she was tagged.

Of course, Representative Oremus is a grown woman, and she should probably know better, but she is certainly not alone in the “utopian” (read: dystopian) vision of a world in which children are taught by, essentially, automatons. Indeed, in many districts throughout South Carolina and throughout the United States, districts are trying harder than ever to “standardize” education.

Standardization, like most educational buzzwords, has had its meaning and connotations stretched in many directions, but at its root it refers to making things (systems of measurement, educational experiences, academic assessments, teachers, classrooms, children’s brains) the same. In this way, it runs up against some of the same— let’s be charitable and call them “philosophical”— issues tackled wildly and haphazardly by the anti-truth bills, like the difference between “equity” and “equality”. The general consensus of educational researchers is that doing the same thing for every student doesn’t achieve the goal of providing equal opportunity for every student. The reasoning behind this is partly based on years of research, and partly based on— Have you ever actually tried doing exactly the same thing with a bunch of different kids, without any accounting for individual preferences, needs, and interests? It doesn’t work that way!

Representative Oremus at one point told Superintendent Spearman,

And I think that’s where— that in [sic] lies the problem: is all these other sources are being introduced to our children, not from a textbook, from whatever just this teacher decides, and it could be tainted one way or the other. So that’s kinda where we are and why we have so many definitions of it [CRT?], sometimes it’s called “Social Emotional Learning” and I know that is happening in classrooms, um, because I’ve gotten letters from principals saying their excited to bring that out and roll that out. So, where is the consistency? Not everything is getting, you know, looked at, at the coursework, and you’re not monitoring every teacher, and I know there’s 55,000 teachers out there and they’re all gonna be teaching something different, but where do we step in and stop at that and say, “Okay, you don’t have that ability anymore. I mean you might be teachin’ something that should be left to the parents”?

The idea of a dry, emotionless version of history without perspective runs counter to what we know about how children learn. Superintendent Spearman correctly defended the way modern teachers have moved away from “starting at the beginning of the textbook and trying to get to the end”. As sociology professor and researcher James Loewen writes in Lies My Teacher Told Me,

Students are right: the books are boring. The stories that history textbooks tell are predictable; every problem has already been solved or is about to be solved. Textbooks exclude conflict or real suspense. They leave out anything that might reflect badly upon our national character. When they try for drama, they achieve only melodrama, because readers know that everything will turn out fine in the end. “Despite setbacks, the United States overcame these challenges,” in the words of one textbook. Most authors of history textbooks don’t even try for melodrama. Instead, they write in a tone that if hear aloud might be described as “mumbling lecturer”. No wonder students lose interest.

Parents being empowered as curriculum experts aside, the idea of using a standardization method— whether a textbook or a computerized test— to give all students the same experiences in class is reminiscent of the goal of achieving egalitarianism by making everyone the same which is a favorite target of dystopian writers.

Kurt Vonnegut skewered it in “Harrison Bergeron,” with its Handicapper General lethally enforcing the status quo of keeping everyone’s intelligence, attractiveness, and physical abilities from reaching beyond the lowest common denominator.

Yevgeny Zamyatin skewered it in WE, a novel that can perhaps be best read as a viscous takedown of Taylorism, and which is in a way the inverse of Metropolis, dealing with human beings turned into automatons by an efficiency-obsessed society that demonizes free will.

Even the one-time philosopher queen of right-wing pundits/ libertarians/ edgelords, Ayn Rand (someone I am almost sure at least some of the committee members would at least pretend to have read) viscously satirizes the idea of extreme equality in her dystopian-science-fiction novel Anthem. (Rand’s novel was probably a ripoff of Zamyatin’s WE and definitely a ripoff of Stephen Vincent Benét’s “By the Waters of Babylon”. The point is that while she might have approved of the cut-and-paste plagiarism of the process of writing the bills, Rand probably would have had only contempt for the idea of spoon-feeding only the most pre-processed history.)

I’m not generally a conspiracy theorist, but when educators and thinkers wonder if the real purpose of narrowing and standardizing curricula is to narrow and standardize workers to make them more docile and obedient, I’m starting to buy it more and more. Since 1983’s Nation at Risk report, US policymakers have been hell-bent on doing to kids’ brains and school experiences what they are unwilling to do with the Metric system. The obsession with making sure we beat non-democracies at the kinds of tests the don’t value out-of-the-box thinking is a troubling one, and I would argue that our Post-Truth™ era owes a lot to 38 years spent moving ever-closer to a goal of teaching nothing that can’t be reduced to a multiple choice test question.

A book I’d really recommend for anyone wanting to learn more about the way standardization works to uphold the illusion of “meritocracy” is Peter Sacks’ Standardized Minds. I did not find it coincidental at all that one forbidden concepts according to another main source of the language of the bills, NAS, is that “meritocracy or traits such as a hard work ethic are racist or sexist, or were created by members of a particular race to oppress members of another race”. When we start to consider who does best with standardized testing and other forms of standardization, and if we are not allowed to use any of the forbidden concepts (like the fact of systemic racism) to analyze who benefits from those students doing well, it becomes pretty clear why the same people who like standardization often also want to pretend that we live in a completely merit-based system, an idea that is only really plausible if we ignore systemic racism, redlining, the disproportionate imprisonment of people of color, and other, you know, forbidden concepts.

Making the experience of every student the same is a dream that apparently unites Melissa Oremus with many would-be-progressive school leaders. In discussions with educational leaders at both the local and state level, I have heard a similar refrain across the political spectrum: yeah, standardized tests and learning are awful— they make kids hate school, they drive the best teachers out of teaching, they take up a lot of valuable instructional time— but what alternative do we have? (For answers to that, I highly recommend researcher Jack Schneider’s work on alternative assessments. Among other possible solutions, Schneider recommends, in his book Beyond Test Scores, a measurement framework that includes data on “Teachers and the Teaching Environment,” “School Culture,” “Resources,” “Academic Learning,” and “Character and Well-Being”. You know, the things the public actually cares about.)

Senator Shane Massey, sponsor of the leading voucher bill in the state, got caught in the standardized test trap last week, when he supported an amendment that would allow all students in “underperforming schools” to qualify for vouchers, but under questioning acknowledged that schools are defined as “underperforming” largely or totally through test scores, and that the tests are “bad”.

Senate Education Chair Greg Hembree once told me, after a committee hearing, that, yeah, everyone keeps saying the tests are bad or racially-biased, but then why are the same parts of the state always scoring badly on them? Again, if you remove forbidden concepts like redlining, systemic racism, etc., you’re only left with the faulty conclusion that it’s not because the state has perennially neglected and historically segregated those areas, so I guess it has to be because everyone in SC’s so-called “Corridor of Shame” is just really bad at tests?

The reason standardization is so pernicious is that even people who want to help historically underserved students and communities often drink the Kool-Aid when it comes to the magic bullet of making every student and teacher do the same thing in the same way (especially when doing so involves the aid of fancy, expensive programs and software, and most especially when the programs and software are so expensive that the companies that provide them can afford reps and lobbyists to dazzle everyone with promises of incredible test scores and centralized control from the district office).

I have heard at least one superintendent rail against standardized tests with one breath, only to defend with the next breath the district’s purchase of a heavily standardized online “benchmark” software platform called MasteryConnect, which is primarily designed to pull from a “Case Item Bank” of standardized test questions created by a company called TE21. In essence, the idea of MasteryConnect is to give students computerized, standardized-test-like items on a weekly basis throughout the school year in order to prepare them for computerized, standardized assessments given by the state each year (the ones that Republican Shane Massey and Democrat Darrell Jackson agreed, in that subcommittee meeting on the voucher bill, were “awful”).

The general consensus among every teacher I know, and some district office staff, is that the Case Item Bank is garbage, pulling primarily low-interest public domain passages (think, a Benjamin Franklin essay on topsoil, or something) and pairing them with questions created by faceless employees of a fairly secretive and opaque for-profit company.

Incidentally, the chosen passages seem to be getting even blander the more we keep arguing about forbidden concepts, perhaps because vendors want to find texts that couldn’t possibly offend anyone, which results in the literary equivalent of elevator music.

I would argue that while districts may value the idea that they can easily pull “data” on how every kid in the district did on the same question, this “data” is of no value unless the question is actually a good one that measures what we want it to know. As Schneider writes, “The reality is that most criticism has been leveled not at collection of data per se but at the collection of incomplete or misrepresentative data.”

But even more than that, making automated, standardized questioning a regular part of the school week sends a very clear message to students and teachers that what we value is the test, and, even more than that, a computerized, automated delivery system for the test that treats every student exactly the same, even though they are not exactly the same.

The superintendent I mentioned above made the argument to me once that standardization in this way (although the superintendent did not use that word) somehow made education more equitable, relating stories about teachers in different schools who were teaching social studies but choosing to focus heavily on different periods of history, which was evidently a problem for reasons I didn’t quite grasp, but which Melissa Oremus would probably enthusiastically co-sign. I’m sure that superintendent, who is deeply concerned with equity and inclusion, would be disturbed at how similar his concerns ended up being to Oremus’ but that seems to be the Faustian bargain we strike with efficiency and scientific management: standardize minds enough, and we might reach the same result no matter why we set out on the road to standardization.

Were the students, the superintendent also worried, getting an equitable education, if the teachers were doing such different things? And what about students with “bad” teachers? And would making more and more of the teachers’ decisions and materials controllable by the district office not give more students the opportunity for the same quality of education? (One way of looking at this plan, of course, is that it would work by lowering the quality of education in every classroom to the same low level, and would ignore the specific learning needs of the individual students, the ones the teachers were hired to assess and address in the first place.)

This superintendent was not much interested in my argument that overly standardizing and Taylorizing learning would also potentially drive away the district’s best teachers. In the superintendent’s opinion, if teachers couldn’t adapt to the district plan, perhaps they should move on to another job. His prediction was that the bad teachers would leave first, although in my experience it has been the most innovative, most engaged, most effective teachers who are most unwilling to work in a heavily standardized system.

In any case, given SC’s historic teacher recruitment and retention crisis, it is likely that many of the teachers who didn’t want to get with the program in that district did leave. After all, most people don’t go into education because they want to be robots, or because they want to turn students into widgets on an assembly line. In January’s SC Teacher survey, 55% of respondents identified “Because I was dissatisfied with the administration during the most recent school year” as an important factor in deciding to leave the profession, with 23% saying this reason was “extremely important” and 9% saying it was “very important”.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Other Duties (as assigned) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.