Book Bans in the Real World

What FOIA requests reveal about the kinds of books being challenged in SC schools, and about who is making the challenges.

Pledge Drive: This work is possible because of subscribers and donors.

Starting before the winter holidays, I began to make a series of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to local school districts. I don’t really have the capacity as a single (mostly unpaid) researcher to do this with every district, so I tried to focus on districts in areas with large numbers of publicized book challenges/ ban, and/ or large numbers of Freedom Caucus/ Moms for Liberty types (who seem to be driving these challenges and bans).

As more districts have made headlines for large numbers of challenges, and/ or their responses to them, I have added these to the list.

Updated 2/11: Most districts I contacted responded quickly (usually within a few days) and provided the information for free. Anderson 1 elected to charge a relatively small fee for the information, but I responded with a further explanation of why I think the information is in the public interest and easy to access, and should be provided free of charge. A few other districts which I contacted later have yet to respond (see folder below).

For anyone interested in FOIAing more districts, the language I used was generally something like this:

Good [morning/ afternoon],

Pursuant to the South Carolina Freedom of Information Act, I'd like to request records relating to book challenges and removals in the district, including any challenge forms and a list of books which have been challenged. Thank you very much for your time and attention! Please let me know if you need any additional information.

I plan to share this information with taxpayers who are seeking to give feedback on proposed regulations being considered by the South Carolina Board of Education. These regulations will impact all public schools in the state, including [name of school district], and officials in some districts have already publicly tied current processes for considering book challenges to these proposed regulations.

This information will not be used for any commercial solicitation. Because this information is requested in the public interest, I ask that all fees be waived.

Sincerely…

Paul Bowers (now with SC-ACLU) has shared some great resources about how to do FOIA requests on his blog.

This folder (which I’ll update as I get more responses), contains redacted versions of all of the information I received from the eight districts which have responded.

If anyone out there does get back a formal response for a FOIA request for any districts I haven’t contacted yet, I would love to include those in this resource.

So what do these FOIA requests reveal?

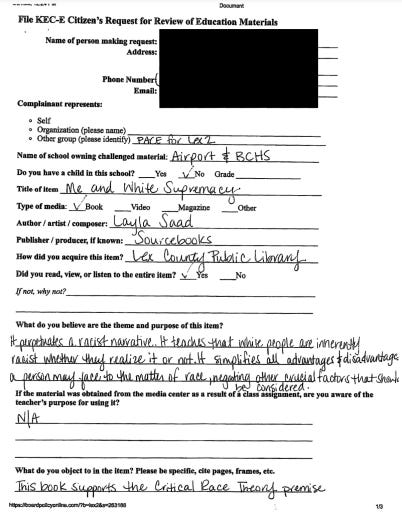

A very small number of people and groups are making book challenges on behalf of the rest of us. For example, every one of the Lexington District 2 challenges was made by members of a Moms for Liberty- like group called “PACE for Lexington 2”. All of the challenges provided by Greenville Schools were from one person. All of the challenges in Horry County were from the local Moms for Liberty chair. And although I haven’t received a response to my request last week with Dorchester District 2, one community member there (who was not a district parent or student) filed a challenge against 673 books via email. One person brought every challenge in Greenville School District, writing on each form, “I don’t have nearly enough time to read every book that is on the current list,” yet frequently alleging that the district wasn’t providing balanced/ opposing views for books like Dark Money and Nickel and Dimed.

Many of these challenges rely heavily on other people to do the actual reading. In Lexington 2, all but three of the fourteen challenges I initially reviewed were from a list provided by BookLooks. Many complaints even owned up to not reading the books before challenging them. For example, the author of a complaint against Rise Up!: How You Can Join the Fight Against White Supremacy shared that, “I didn’t read much further than the introduction for the author to reveal her purpose, motives, and activism.” A complainant in Pickens circled “No” next to a question about whether they had read the book (Perks of Being a Wallflower), and wrote, in answer to another question, “I do not have a recommendation. There should be nothing of this ‘quality’ available to our students.”

Many (and probably most) of the challenges are against books that deal with race in America, and/ or LGBTQ+ themes. While I haven’t had time to closely analyze all of the challenges— almost 100 of which are from one district, Beaufort Schools— the emerging trend seems to be that books like Dear Martin and Stamped have received disproportionate attention and challenges (and have resulted in disproportionate reactions from the districts), as have books that deal with what BookLooks calls “gender ideology” (a nonsense term that broadly means, “anything acknowledging the existence and experiences of LGBTQ+ people,” since BookLooks and others have labeled books like Anne Frank’s Diary: A Graphic Memoir as potentially containing “Explicit Gender Ideologies”. The Greenville challenger objected to the book Talking to Strangers on the grounds that it taught students that systemic racism was real, and that opposing viewpoints weren’t provided. Several complaints from PACE for Lex2 claim books like A Good Kind of Trouble foment what one challenger calls “racial unrest”.

Many of the challenges are political in nature. The lone Greenville challenger complained that books like Nickel and Dimed promoted “socialism” and that Dark Money was an attack on “the Republican Party, in particular the Koch Brothers”. While as a research teacher, I can understand the call for opposing viewpoints that this challenger makes on each form, it’s also not logical to turn every issue into a two-sided conversation. Racism, wealth inequality, and political corruption are topics that can and should involve many perspectives, but often what book challengers seem to be doing is employing a black-or-white fallacy where if two sides of an argument don’t have equally strong representatives, students shouldn’t be allowed to engage in the argument at all. (An extreme example would be requiring pro-Nazi arguments in order to discuss anti-Nazi arguments.)

The book challenges represent a major weakness in current approaches to allowing public input on district text selection, with districts generally allowing formal challenges from individuals, often with little or no substance, to trigger a process whereby district employees— usually librarians— have to spend significant amounts of time and effort to “review” books that almost always went through a review process before they were adopted in the first place.

What if we had this same mess, but at the state level, too?

When the State Board of Education meets on February 13, they will be discussing a proposed regulation1 that codifies this problem into state law. As written, the regulation allows any person living in South Carolina to challenge any text based on extremely broad, overly vague criteria (such as the requirement that the language and content meet FCC guidelines— which, as the FCC itself describes them, employ an “I know it if I see it” standard that can be inconsistent and inscrutable.) As the complaints provided by South Carolina districts demonstrate, it is unlikely that complainants will have to meet even the incredibly low standard of having actually read or viewed the content themselves in order to potentially trigger a ban in each district. And if a district decision is appealed to the State Board, an individual can effectively ban a book— any book that they argue meets these very broad guidelines— for the entire state.

Of course, South Carolina is not alone in this absurdity. Across the country, states are proposing and passing book ban legislation and regulations— although South Carolina’s proposed regulation goes further than any I have encountered in its broadness and in its deputizing of any individual in the state to influence the reading options of every student in the state.

What can you do?

If you are in South Carolina, please contact your State Board of Education member (you can find their contact information at the end of this email template; contact information on the State Board website is not always up-to-date) and urge them not to support the regulation as currently written. If you’re able to attend the final meeting on these regulations, please do so. (The full board meets at 1:00 on February 13; more details will be available at some point on the rarely-updated Board website.)

If board members are open to amendment suggestions, mine would be that they require challengers to be connected to the schools where they are bringing challenges— parents, students, and staff members. I would also suggest that individuals and groups be limited to a reasonable number of challenges at once; otherwise, challenges become a tool to obstruct the work of the district, as even though most books are eventually returned to shelves, it takes months for committees to read each book. Older students should also be involved in the process, serving on book review committees. And at the very least, would-be censors should have to provide evidence that they actually read the books in order for their challenges to be heard.

Of course, it’s hard to believe that most of these challenges are made in good faith. After all, if parents were concerned about protecting their own children, I would think they would be calling for the ability to opt their own children out of readings— something else the regulation could require— rather than challenging massive numbers of books that most community members do not seem to have any problem with.

If you’re not in South Carolina, there are likely challenges in your area, too. Now is the time for all of us to be proactive, to not remain a silent majority on the topic of book bans, which most Americans don’t support.

Although it’s possible the Board has already made amendments to the regulation, it doesn’t seem to be posted anywhere online, and requests for a copy have gone unanswered. Here is a copy of the first-published version, typos and all.