Book Bans in the Real World (Part II)

Looking beyond the fevered rhetoric to see who is really challenging books, and what they are challenging.

Earlier this year, I began requesting information from South Carolina school districts to find out, where possible, who is actually challenging books in the districts, and which books they are challenging. Most districts responded quickly to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, and most of these required no payment for providing the requested information.

As the production of documents (collected in this folder) shows, there are usually only a few pages— if any— of documents to provide (with the notable exceptions of districts like Beaufort, which received almost 100 challenges from a single person, and Dorchester 2, which received almost 600 challenges from a single person, and which has so far evidently neglected to respond to my January FOIA request).

While state law allows public entities to collect fees to cover the cost of searching documents, I assume many districts felt it was in the public interest, and in their own interest, to have transparency about what exactly is happening here.

There are, of course, limits to what FOIA requests can show us. For starters, at best they can only capture records which are actually controlled by the district. In Anderson One, for example, Moms for Liberty activists claimed through social media that they had private conversations with at least one school principal in the district, a conversation they said elicited a promise by the principal to remove book without a formal complaint. If true, this would mean there was in effect a challenge that isn’t reflected in the Anderson One production of documents, though a district official denied having any evidence of such a conversation.

In some school districts, including Charleston and Anderson One, district officials elected to charge small fees. Charleston took by far the longest to respond to a FOIA request, first asking for a small fee and then taking nearly an additional month to provide what amounted to thirteen electronic documents (available here).

Interestingly, most districts did not redact the documents they provided, meaning the original versions often reveal the names, and even phone numbers and addresses, of both public employees like administrators and teachers, and complainants. This may be a general district practice, but it is my understanding that agencies are allowed under state law to remove at least some identifying information (as I have done in most cases).

While it’s useful to see who is making challenges, and to be able to connect these to specific originations— for example, PACE for Lex 2, a Moms-for-Liberty- adjacent group which made every one of the complaints provided by Lexington School District 2— I have redacted names of individuals unless they are public figures.

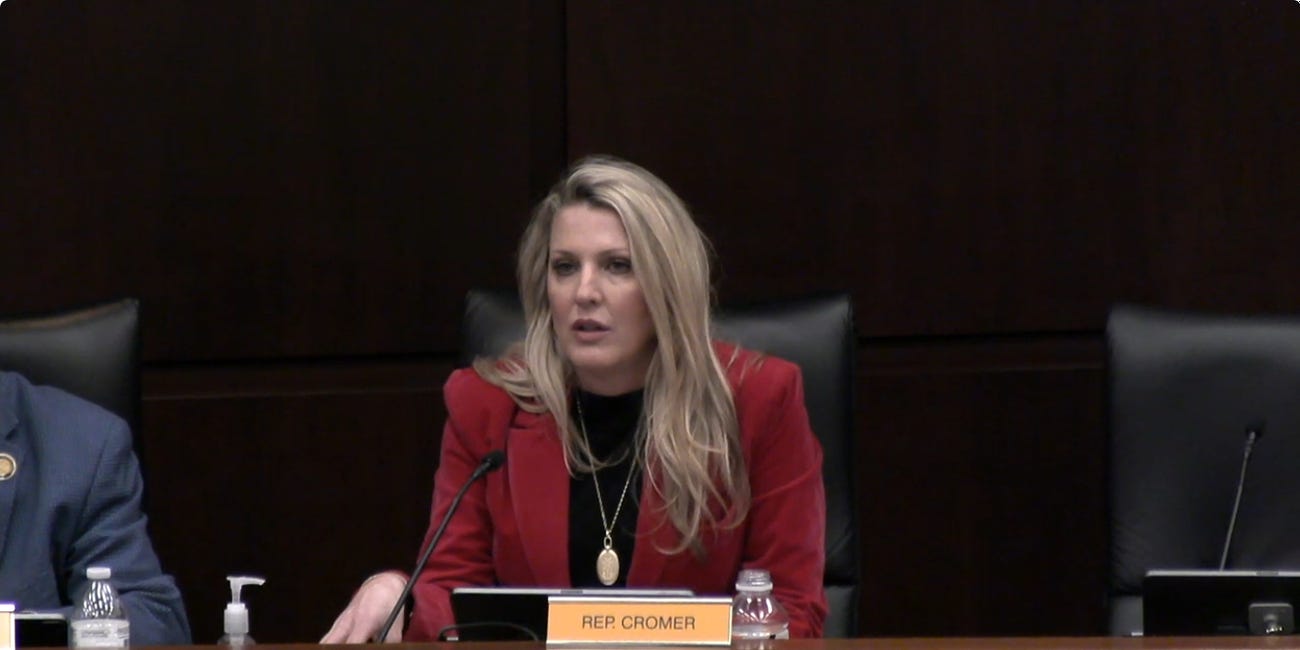

As state representative April Cromer’s request, which resulted in a massive 17,000-page document production by Anderson One, shows, the double-edged sword of FOIA requests is that while they are ideally to be used to provide sunlight into processes that legitimately interest the public, they can be used by bad faith individuals to dox and encourage the harassment of individuals. That said, I’m willing to share unredacted versions of these FOIA productions, including names and other relevant information (which probably would not include the phone numbers or addresses of complainants or anyone else) with journalists or others with a legitimate interest in understanding who is making these complaints, or who is the target of said complaints.

So what do the document productions show?

There seems to have been a shift in media coverage around book bans in recent months, from some frankly gullible early coverage that seemed to take groups like Moms for Liberty at their words that a significant number of parents are outraged at “woke indoctrination”. But as time has gone on, the narrative has begun to reflect the reality these FOIA requests confirm: most people aren’t challenging books in South Carolina, and this seems to hold true across the country.

The narrative has shifted so much, in fact, that some of its major instigators, like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, have begun to acknowledge publicly that maybe allowing political organizations carte blanche to ban books was a dumb move.

Since the first piece I wrote on state book challenges, I was able— through the help of some kind donors— to pay for some more requests. Most of the information from these requests has been covered in previous pieces, but I did want to spend some time on the small number of documents I received from Charleston Schools.

Charleston

If the documents provided by Charleston’s school district tell the complete story, or something close to it, only three books have been challenged in the district in recent years.

The first of the challenged books is Pride: The Story of Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag (available in full as a free read aloud by the author).

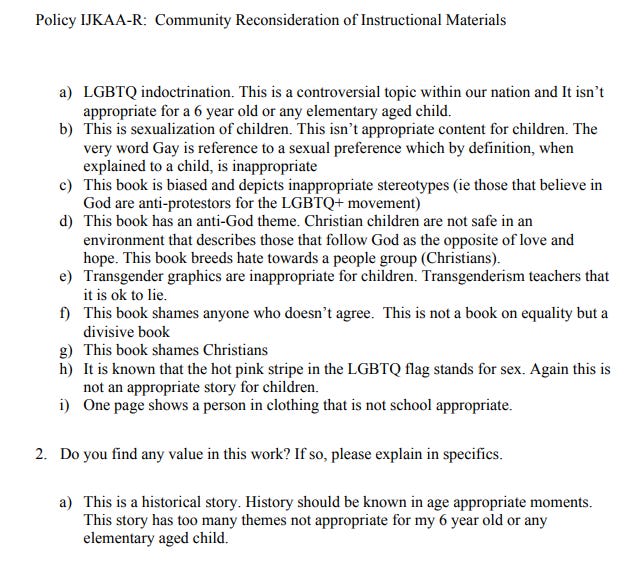

The complainant who challenged Pride makes a number of arguments that are hard to sustain (or even follow) after reading the actual book.

First, she starts with an accusation, which will be familiar to anyone following the evolution of the general book ban narrative, of “LGBTQ indoctrination” (this is, effectively, 2024’s answer to “CRT”: a weasel word that stands in for any kind of vague stuff about the existence of gay people, and by extension anything else book banners might not like).

Like Anne Frank’s Diary, another book challenged across the country, often for containing LGBTQ+ themes, Pride can’t really be argued to be indoctrinating anyone about anything. The book’s tone is consistently gentle— and in my mind completely appropriate to young audiences— and the only idea it emphasizes is that everyone (gasp!) should be able to live freely.

The complaint also uses a single sign held by a protester in one image, reading “God says NO” to create a narrative that the story is “anti-God” or “shames Christians”. (Imagine reading, for example, a slave narrative, and arguing that because author’s frequently highlighted the religious hypocrisy of slaveowners, slave narratives are somehow anti-Christian).

She also argues that the use of texts like this one— which simply retells a series of historical events and acknowledges that gay people do exist— is to support sexually “grooming” young children. Aside from the fact that this is, again, a gentle children’s book simply recounting the story of the flag’s creation, it is not indicated by either the complaint or the district’s response that anyone coerced or even encouraged the complainant’s daughter to read Pride.

A statement provided by the district for the librarian to read includes an excellent response to the parent’s request that the book be removed from all district text collections for these reasons:

A recommendation to keep this book on the shelf is not intended to negate your beliefs, but your beliefs can only dictate access for your own children, just as other parents can only make decisions for their children, not yours. A note has been added to both of your children’s accounts so that they will not be able to check out books containing LGBTQ content.

Unsurprisingly, given the general trends throughout the state and country, two of the Charleston complaints, those against Pride and This One Summer, make often-strained references to “sexuality” or “sexual content”. This is very much in keeping with the current playbook of Moms for Liberty and related groups, which are attempting to weaponize legal prohibitions against providing obscenity and pornography (both of which have legal definitions that do not include “acknowledging the existence of gay people”) against books that they don’t like for various reasons.

I can’t help but associate this kind of loophole logic with “literacy tests” and other ways of skirting constitutional prohibitions and requirements in order to target or oppress specific marginalized groups.

The third complaint, against the book Ivy and Bean, also contains the frankly hilarious sentence below:

I certainly don’t want to make light of what might have frightened this complainant’s child during the first- grade read aloud described in the complaint, but if this is the bar for removing a text from school libraries for all students, what exactly are we trying to accomplish, and how many books are we willing to remove from the access of all children to do it?

As with other districts, I have redacted the names of both employees and complainants, but I will note an observation that a disproportionate number of complainants in South Carolina, for whatever reason, work in real estate. In Charleston, this applies to every complainant. The individual who challenged This One Summer is evidently an agent for Keller Williams, while the individual who challenged Ivy and Bean seems to work for Olivieri Management, and the individual who challenged Pride seems to work for King Tide Real Estate.

Make of that what you will.

In general, Charleston Schools seem to have handled these complaints in the best possible ways, all things considered. The district took the complaints seriously, even when the complainants do not seem to have been acting in good faith. It convened committees that included both content experts— librarians and teachers— and multiple parents. Documents indicate the district also invited the complainants, themselves, to sit on these committees, although it seems like in at least one case the complainant showed no interest in doing so.

And, in the end, the district upheld the decisions which had already been made by content experts to adopt these texts. It respected the individual wishes of parents for their own children, and explicitly did not allow these three realtors to make sweeping decisions about what every student in the district could access and read.

Unfortunately, in South Carolina and other states, officials are working hard to make an end-run around these kinds of reasonable community decisions, and seem to be willfully about two years behind learning anything from what has already happened in states like Florida. Last week, there was a meeting to discuss Superintendent Ellen Weaver’s proposed regulation giving power to make these determinations to the State Board of Education and essentially negating district-level processes for considering complaints1. The meeting time was abruptly changed, making it impossible for many interested parties to attend.

A conference committee meeting for another piece of state-level censorship policy, House Bill 3728, is scheduled for tomorrow. (Update: this meeting has been cancelled, but you can contact the committee members before the next meeting by using this form.)

I should say that I’m conflicted about the regulation. As currently amended, things could be a lot worse. And given that some districts in South Carolina have not created fair or reasonable processes for considering book challenges, it might not be the worst thing to have an even-handed state-level regulation. Unfortunately, Weaver’s reg was probably never intended to be that, and would likely need a lot more work as it moves through the state legislature— where it may have already stalled out for the session— in order to be useful.