Are school administrations responsible for school shootings?

Content warning: descriptions of gun violence.

Plaintiff goes so far as to claim that she reasonably anticipated that “she would be working with young [elementary school] children who posed no danger to her.” [Complaint ¶36]. While in an ideal world, young children would not pose any danger to others, including their teachers, this is sadly not reality.

As you’ve probably heard, Abby Zwerner, the former Virginia elementary school teacher who was shot by her student two years ago, won a $10 million jury verdict in her lawsuit against her former employer, and specifically against her former assistant principal, over the shooting.

The student’s mother previously pled guilty to felony child neglect, and received a two-year sentence. (According to Zwerner’s complaint against the school district, the gun belonged to the student’s parents.)

A recent study by researchers at the University of South Carolina found that about 42% of the guns used in school shooting incidents belonged to relatives of the shooters. The finding, researchers said, supported the implementation of safe storage laws; Virginia does not have such a law. (Neither does South Carolina.)

The 6-year-old student shot Zwerner during class, while she was sitting at a reading table in the classroom. The bullet passed through her hand and lodged in her chest, where it remains. Her lung collapsed; she would go on to require six surgeries to repair the damage. According to Zwerner, the school’s administration received multiple reports that the student who shot her had been behaving strangely, that he had a history of violent behavior, and that he might have a weapon. School employees did reportedly search the student’s backpack before the shooting, but did not find a weapon.

I don’t have a lot to add to the reporting that has already been done on that case, but as someone who used to regularly wonder if I or someone I loved would die in a school classroom, I do have a lot of thoughts and feelings.

The central question the case raised was whether school officials and administrators are responsible for preventing teachers from being shot. And that is a valid question, even if it probably doesn’t have any easy answers.

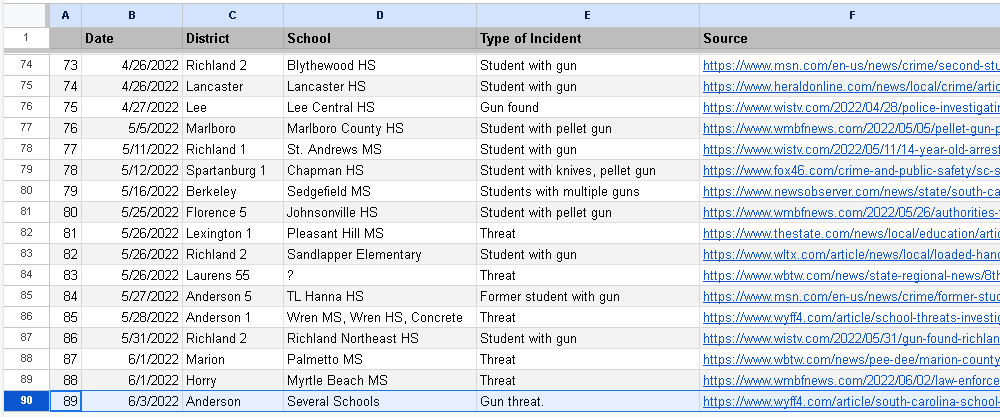

For a few years, I tracked reported incidents involving guns on South Carolina K-12 school campuses. In one year alone, there were 89 reported incidents of people— usually students— bringing, threatening to bring, or using weapons— most often guns— to South Carolina schools. (Among people who know education in the state, the consensus was that these were significantly underreported, that schools and districts had a perverse incentive to cover up or obfuscate information about students bringing deadly weapons to school. In other words, there are probably significantly more than 89 guns on school campuses each year in South Carolina.)

In many of those reported cases, educators or administrators only found out that there were guns on their campuses because of reports from other students. In my own experience, we almost never knew about a weapon unless a child or young adult saw it and had the good sense and courage to tell someone.

I won’t Monday morning quarterback the shooting. I would hate to be in the shoes of the administration at Zwerner’s old school, and especially in the shoes of the assistant principal, and I’m sure no one involved wanted a teacher to be shot.

I would hate, even more, to be a teacher who was shot by a student after seeking help from an administrator, and being given, as Zwerner says she was given “no response” after telling the assistant principal that the student who shot her was in a “violent mood” on the day of the shooting.

Zwerner’s complaint alleged that the student had a long history of violence “at home and at school” and that he had been removed from a previous school after choking a teacher. It also claimed that a few days before the shooting, the student had taken and smashed Zwerner’s cellphone, and that when she called for school security, no one responded. (Based on my years as a teacher, I find this unfortunately easy to believe.)

It is, of course, important to note that schools are often limited in their options for dealing with students with chronic behavior problems, and that there are good reasons for avoiding exclusionary discipline as much as possible. On the other hand, according to Zwerner’s complaint, the assistant principal had an established tendency to “ignore and downplay concerns expressed by teachers,” and to send students sent to her office for misbehavior back to class with “candy”.

Of course, while this all sounds plausible, I don’t know if it’s true. But what this particular high-profile case represents, to me, is a reminder of all of the things we know, but have not appropriately addressed, about gun violence:

We know storing guns safely makes them less accessible to children and other school shooters. (And yet many states do not have safe storage laws in place.)

We know that having more people in schools who have the time and training to get to know students creates more opportunities for an adult to realize that a student may be in crisis, or may be planning something dangerous. (And yet South Carolina, like many other states, continues to underfund schools, including by staffing them with counselors at far below the ratios recommended by counseling associations.)

We know that the research supporting popular security theater measures, like additional school resource officers and metal detectors, is weak at best. In fact, making schools more like prisons likely harms students and may even increase misbehavior.

We know that funding common-sense infrastructure improvements (like well-functioning door locks) can have a positive impact on school safety.

But mostly, what we do with this knowledge seems to be very little until another high-profile school shooting jolts us out of our sleep long enough to— in the best case scenarios— briefly take a research-supported step towards addressing the issue.

My last year as a teacher was perhaps the only time I was able to convince anyone to meaningfully address safety at the whole-school level. For years, I had complained to school administrators about the poorly-designed locks on our classroom doors. These locks could only be engaged using a key; when anyone left the classroom, the locks disengaged and the doors stayed unlocked. Administrators repeatedly said they would take the issue to the district; whether they did so or not, the problem was never addressed. (When I contacted the district’s facilities coordinator, he repeatedly made excuses and explained away my concerns.)

Then, in the wake of the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, which famously involved a malfunctioning lock, I tried one more time. I emailed the entire school board— something that is easier to do when you aren’t planning to return to the district— and thanked them for recent moves to address safety. But I also urged them to update the door locks.

The next year, after I had left teaching, my colleagues told me that in response to the email, all of the locks in the building had been updated.

The clear lesson, for me, was that schools are unlikely to become safer without persistent effort, and in my case it took annoying a lot of people— especially the facilities coordinator— for a long time (years, in this case). My email to the school board was at least the third one I’d sent. And I think it’s only because I explicitly referenced the Uvalde shooting that it finally sunk in that something really terrible might happen if the district didn’t address the problem. (It may have helped that I pointed out that the district had sold a bond referendum to tax payers a few years earlier partly on the promise of facility upgrades to make schools safer; the bond referendum explicitly included money for “more secure entrances,” as I pointed out in my email.)

I ended that email by writing,

On a personal note, not feeling that my students, my friends, my wife (who is also leaving the district), or myself are safe in the school building was a significant factor in my deciding not to sign my contract this year, and I know there are others who feel the same. Of course, there are many factors related to school safety which are not under the district’s control, but that makes it all the more urgent to address those which are. I believe in this district, and I know it can be, and often is, a great place to learn and work, but safety should be our first priority, and until we take small but meaningful steps like replacing outdated locks from 20 years ago, it doesn’t feel like a priority.

I’m glad the district listened, even if they did so belatedly. But sometimes acting belatedly gets people hurt or killed. And whether or not that’s what happened in the case of Abby Zwerner, I hope the high-dollar judgement does encourage districts across the country to try to act more proactively than many of them have been doing to make students and staff safer.